Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

- Panel Report

- Summary

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Project and Sustainable Development

- 3 Project Need and Resource Stewardship

- 4 Land Claims and Impact and Benefit Agreements

- 5 Air Quality

- 6 Tailings, Mine Rock and Site Water Management

- 7 Contaminants in the Environment

- 8 Freshwater Fish and Fish Habitat

- 9 Marine Environment: Land-Based Effects

- 10 Marine Environment: Shipping

- 11 Marine Mammals

- 12 Terrestrial Environment and Wildlife

- 13 Birds

- 14 Aboriginal Land Use and Historical Resources

- 15 Employment and Business

- 16 Family and Community Life, and Public Services

- 17 Environmental Management

- 18 Recommendations

- Appendix A: Panel Members

- Appendix B: List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Appendix C: Memorandum of Understanding

- Appendix D: Transcript of Proceedings

- Appendix E: Acknowledgements

Voisey's Bay Mine and Mill Environmental Assessment Panel Report

Panel Report

Transmittal Letter

Mr. William Barbour

President, Labrador Inuit Association

P.O. Box 70

Nain, Labrador A0P 1L0

Mr. David Nuke

President, Innu Nation

P.O. Box 119

Sheshatshiu, Labrador A0P 1M0

Honourable Oliver Langdon

Minister of Environment and Labour

P.O. Box 8700

St. John's, Newfoundland A1B 4J6

Honourable Christine Stewart

Minister of the Environment

Les Terrasses de la Chaudière, 28th Floor

10 Wellington Street

Hull, Quebec K1A 0H3

Honourable Walter Noel

Minister of Intergovernmental Affairs

P.O. Box 8700

St. John's, Newfoundland A1B 4J6

Honourable David Anderson

Minister of Fisheries and Oceans

15th Floor, 200 Kent Street

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0E6

Dear Sirs and Madam:

In accordance with the mandate issued January 31, 1997, the Joint Environmental Assessment Panel has completed its review of the Voisey's Bay Mine and Mill Development as proposed by the Voisey's Bay Nickel Company.

We are pleased to submit the Panel report for your consideration.

Respectfully,

Lesley Griffiths (Chairperson)

Samuel Metcalfe

Lorraine Michael

Charles Pelley

Peter Usher

Summary

The Project

The Voisey's Bay Nickel Company (VBNC) proposes to mine nickel, together with some copper and cobalt, at a location in northern Labrador, 35 km south of Nain and 79 km north of Utshimassits (Davis Inlet). VBNC would start by mining 32 million tonnes of ore from an open pit, while carrying out more exploration to find out exactly how much ore is underground. VBNC would then develop an underground mine, where it hopes to be able to mine another 118 million tonnes.

VBNC would process the ore in a mill on site to produce concentrates. The main waste product coming out of the mill would be finely ground rock called tailings. The tailings, together with some of the waste rock excavated from the open pit and the underground mine, would be stored under water in two tailings basins made from existing lakes. This would prevent the tailings and rock from being in contact with both air and water simultaneously, which would cause them to release acid.

VBNC would transport the concentrates from Edward's Cove by ship to another location, as yet undecided, for further processing. At first, the ships would not have to travel through landfast ice, but eventually VBNC would want to ship year round, except when the ice is forming or in the early spring.

During the hearings, VBNC said that the Project would create 570 jobs during construction, 420 jobs in the open pit phase and 950 jobs in the underground phase. Only about half of the workers would be on site at any one time, because they would work and live at the site for two weeks, and then return home for two weeks. VBNC would not build a new town at the mine site.

The Review Process

In January 1997, the federal and provincial governments, the Labrador Inuit Association (LIA) and the Innu Nation signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) setting out how the environmental effects of the proposed Voisey's Bay Mine and Mill Project would be reviewed. A five-person panel was appointed to carry out this review and prepare this report. The panel members are Ms. Lesley Griffiths (Chairperson), Dr. Peter Usher, Dr. Charles Pelley, Ms. Lorraine Michael, and Mr. Samuel Metcalfe.

The Panel held two rounds of public meetings. Scoping sessions took place in spring 1997. The second round, 32 days of public hearings, took place in 10 Labrador communities and in St John's during September, October and November 1998.

The Panel's Overall Conclusion

To reach an overall conclusion about the Project's effects, the Panel asked three main questions, based on the terms of reference in the MOU.

- Would the Project cause serious or irreversible harm to plants and animals and their habitats?

- Would the Project affect country foods or prevent Aboriginal people from harvesting them, either now or in years to come?

- Would the Project bring social and economic benefits to many people in northern Labrador or to only a few, and would these benefits last?

The Panel has very carefully reviewed all aspects of the Project and listened to the opinions of government, Aboriginal organizations and many other people. Based on this review, the Panel has made a number of recommendations about how the Project should be carried out. The Panel has concluded that, provided these recommendations are carried out, the Project would not seriously harm the natural environment, or country foods and people's ability to harvest them. The Panel has also concluded that the Project with a lifespan as described in the EIS has the potential to offer the people of northern Labrador lasting social and economic benefits through employment and business opportunities. Therefore, the Panel has recommended that the Project be allowed to go ahead, as long as the other recommendations in this report are made part of the conditions of approval.

Mine Life, Land Claims, and Impact and Benefit Agreements (IBAs)

The Panel's first three recommendations address some important issues that many presenters spoke about:

- how long the Project would last;

- how it might affect land claims negotiations; and

- the role of impact and benefit agreements (IBAs).

The Panel agrees that the Project must last at least 20-25 years. In this way, more than one generation of people would benefit from the mine. Communities would also have a chance to create new economic development opportunities, based on the increased incomes coming from the Project. Therefore, the Panel has recommended that the Province include conditions in the mining lease to ensure that, if VBNC finds less nickel underground than expected, it would reduce the amount of nickel it takes out each year in order to extend the life of the mine.

LIA, the Innu Nation and many individuals told the Panel that the Project should not go ahead until land claims had been settled. After the Panel started its work, the Supreme Court of Canada issued an important court decision about Aboriginal title and rights across the whole country (the Delgamuukw judgement). The Panel understands this decision to mean that where Aboriginal people have title to their traditional lands, governments have certain obligations if they are going to allow resource development such as the Project to take place on those lands. Governments must ensure that Aboriginal people

- participate in the resource development;

- are properly consulted; and

- receive fair compensation.

The Panel believes governments can best meet those three obligations by settling land claims. The Panel has therefore recommended that, before the Project goes ahead, the federal and provincial governments finalize land claims agreements in principle with LIA and the Innu Nation, and put enforceable interim measures in place until the final agreements are signed.

However, the Panel understands that issues that have nothing to do with the Project could possibly delay the settlement of one or both of the land claims. If this occurs, the Panel has recommended that the two governments, LIA and the Innu Nation negotiate an environmental co-management agreement ensuring that Aboriginal people are still fully consulted about the Voisey's Bay development. Participation and compensation would then have to be delivered through IBAs negotiated between VBNC and the two Aboriginal organizations. The Panel emphasizes that these alternative arrangements should leave Inuit and Innu no worse off than they would be if land claims agreements were in place.

VBNC told the Panel that it intended to avoid or reduce some of the predicted negative effects of the Project and to increase predicted Project benefits through the IBAs. LIA, the Innu Nation and many individuals told the Panel that IBAs must be concluded before the Project starts. The Panel believes that it would be easier for both VBNC and the Aboriginal organizations to negotiate IBAs if land claims agreements were already settled. But, in any event, since the IBAs are an important part of the whole Project, the Panel has recommended that they be in place before the Project is allowed to proceed.

Shipping

Many people told the Panel that taking ships through the landfast ice could make winter travel and hunting hazardous for North Coast residents, and could disturb seals, especially when they are whelping. There were concerns about the effects of possible oil or concentrate spills, if a ship should have an accident along the shipping route. There were also concerns about the effect over time of frequent small oil or concentrate spills getting into the water at the port site in Edward's Cove.

There was considerable discussion about the need to ship in the winter months, based on production rates and VBNC's ability to store concentrates at the site for long periods. VBNC told the Panel that it would not take any ships through landfast ice for at least the first two to three years of the Project, and possibly longer. It also said that it would not ship through landfast ice if it could not do so safely. The Panel agrees with many presenters that there is still considerable uncertainty about the effects of icebreaking along the shipping route. The Panel has recommended that VBNC, before being allowed to ship through landfast ice, should

- together with LIA and regulators, further investigate both the need to ship in the winter, and how breaking landfast ice would affect wildlife and the safety of ice users; and

- negotiate a shipping agreement with LIA to address concerns about winter shipping and other issues.

The Panel has also made recommendations about ensuring that ships navigate to and from Edward's Cove safely, and about preventing marine pollution. The Panel has concluded that the risk of a concentrate or oil spill would be low, provided that VBNC emphasized safety measures. Nevertheless, the Panel has recommended that both VBNC and governments prepare oil spill response plans that could deal with a major oil spill, if necessary.

Air Quality

The main effect of the Project on air would be dust raised by the open pit operation and by haulage trucks along the roads. This dust would get into streams and lakes, and affect water quality. Other air emissions would come from burning fuel, either to generate power or to operate vehicles. The Panel has recommended that VBNC develop a plan to control dust and to reduce the amount of fuel burned by conserving energy.

Tailings, Waste Rock and Site Water Management

During the review, everyone recognized that controlling acid generation in the tailings and waste rock was a critical issue. To do this successfully, VBNC must be able to store a huge volume of tailings and waste rock permanently under water in two tailings basins. Issues discussed during the review included

- alternative methods of storing the tailings and waste rock safely;

- the choice of location for the two tailings basins;

- the design of the dams;

- seepage of contaminated water through and under the dams; and

- the fate of the tailings basins after the mine closed down.

The Panel heard that alternative methods might include using the tailings and waste rock to backfill the open pit or the underground mine, or putting them in the sea (submarine disposal). VBNC told the Panel that it is willing to consider backfilling but would need to complete the underground exploration and get more experience at the site before it could make that decision. The regulators told the Panel that they would not authorize submarine disposal at this time.

The Panel has concluded that VBNC's proposed method of dealing with tailings and waste rock would prevent acid generation from being a problem. The Panel also believes that VBNC has chosen the best locations to reduce environmental impacts (starting with Headwater Pond and then constructing the North Tailings Basin when the underground phase begins). However, the Panel has recommended that VBNC investigate the backfilling option before constructing the North Tailings Basin. By doing this, the company might be able to avoid or delay the need for the second tailings basin.

The Panel has also made recommendations about dam design, water treatment, seepage collection and treatment, and a dam safety inspection and maintenance program for all project phases.

The Project would also produce a large amount of waste rock that should not generate acid because of its different chemistry. VBNC intends to store the non-reactive rock on land. The big concern was that acid-generating rock could end up in these waste dumps if waste is not sorted accurately. The Panel has recommended that VBNC develop reliable ways to sort the two types of waste rock and also contingency plans in case acid does form in the storage piles on land.

The milling operation would require large amounts of water to treat the ore. VBNC proposes to recycle much of the water that passes through the mill. Issues raised during the hearings included

- the need to maximize water recycling in order to reduce the amount of fresh water taken from lakes in the area;

- the water quality in the tailings basins; and

- the effects of putting treatment sludges into the tailings basins.

The Panel has concluded that VBNC should operate the mill in such a way as to produce the best achievable levels of treated wastewater quality. This would require constant monitoring and process management. The Panel has made recommendations about water recycling, pollution prevention and sludge management.

When VBNC finishes mining the open pit, the alternatives would include filling it with tailings or waste rock, or allowing it to flood. The Panel has recommended that VBNC rehabilitate the pit in such a way that it is visually acceptable and ensures that Reid Brook cannot be contaminated, either through surface runoff or groundwater.

Contaminants in the Environment

The Panel has recognized that many people living in the North, because of their experience, are very concerned about the effects of resource developments such as the Project on contaminant levels in country foods. VBNC carried out modelling exercises to predict how metals in the rock, released by mining, might move through air and water and up through the food chain. The Panel has concluded that this Project would be unlikely to release metals into the environment at levels that would cause a hazard to fish, wildlife or humans. But, because of the importance of protecting both the quality of country foods and people's confidence that they are safe to eat, the Panel has recommended that

- VBNC monitor contaminant levels close to the Project site; and

- governments, LIA and the Innu Nation develop a program to monitor contaminant levels throughout northern Labrador.

Freshwater Fish and Fish Habitat

The Project would affect many streams and lakes close to the site through the construction of the two tailings basins, extraction of water for the mill, and the need to divert or alter streamflows. Other influences would include stream crossings, erosion and sedimentation, and dust. VBNC proposes to protect fish and fish habitat, including Reid Brook, by discharging only treated wastewater into the sea and by permanently diverting water from the Headwater Pond tailings basin away from the Reid Brook watershed.

Issues raised during the hearings included

- the Project's effects on arctic char in Reid Brook and nearby streams;

- how much fish habitat would be affected and how VBNC would replace it under DFO's no net loss policy;

- the effects of blasting;

- the combined effects of all Project facilities and activities on Reid Brook; and

- what VBNC should monitor and how.

The Panel has concluded that VBNC's proposed mitigation measures should adequately protect fish habitat in Reid Brook. If monitoring results showed unpredicted effects, the Panel believes that VBNC could and should take additional measures. The Panel was concerned, however, about the possibility that more fish habitat could be affected than predicted if VBNC was not able to maintain at least minimum flows of water in all streams affected by the Project. The Panel also did not receive any information about how VBNC would replace the fish habitat that would be destroyed by the construction of the tailings basins.

The Panel has recommended that VBNC prepare a fish habitat protection report with details on all mitigation measures, and that DFO provide opportunities for the public to comment on VBNC's habitat replacement proposals. Other recommendations address preparation of a special environmental protection plan for Reid Brook, the way in which DFO should apply the no net loss policy to this Project, and monitoring and related studies in Reid Brook and the wider Kogluktokoluk-Ikadlivik-Reid Brook system.

Marine Fish and Fish Habitat

The Project would affect marine water and sediment quality through the discharge of treated wastewater, first into Edward's Cove and later also into Kangeklualuk Bay (the only two discharge points). The Panel agreed with DFO's suggestion that VBNC investigate whether all of the wastewater could be safely discharged into Edward's Cove in order to avoid affecting a second bay. The Panel does not expect that the Project would cause a harmful effect on marine fish habitat, except in a very small area, or on the fish themselves. But the Panel was told that this would be the first time in Canada that a nickel-copper-cobalt milling operation had discharged its effluent into salt water, and so there is limited information about the effects of the combination of these metals in a marine environment. The Panel has therefore recommended new research, together with careful monitoring. The Panel has also recommended that VBNC, throughout the life of the Project, keep working to reduce the total amount of pollutants discharged in the wastewater, even if it is already meeting regulated standards.

Seals, Whales and Polar Bears

The main effects of the Project on seals and whales would likely be noise and ice disturbance caused by shipping. An oil spill could also affect marine mammals. Presenters from both government and the public were concerned that not enough was known about seals and whales in this area of northern Labrador, including population numbers and the habitat they use. Shipping through landfast ice has not happened in this area before, and so there is also some uncertainty about how winter shipping would affect seals. The Panel has recommended that DFO carry out more regional studies on marine mammals to add to the work already done by VBNC, and that VBNC and LIA determine whelping times for ringed seals in order to avoid affecting them at that sensitive time.

The Panel concludes that the Project should not adversely affect polar bears, provided that VBNC works with LIA to develop good plans to manage potential interactions between Project employees and bears. The Panel has also recommended that the provincial and federal governments sort out who has jurisdiction over polar bears off the Labrador coast in order to improve conservation and enforcement.

Plants, Caribou and Black Bears

On land, VBNC focused particularly on predicting the Project's impacts on plant communities, caribou and black bear. The Project would inevitably destroy some plant habitat. VBNC plans to keep this destruction to a minimum and to restore most of the disturbed areas to natural vegetation as soon as possible (not necessarily waiting until the Project closes down). The Panel heard concerns about the possibility of forest fires and about the effects of exploration activity, and has made recommendations to address these.

The Project is located within the range of the George River caribou herd. In some years, caribou have wintered in the Voisey's Bay area. Issues raised at the hearings included the alteration or loss of habitat, and the effects of noise, human presence or icebreaking on the caribou's movements. The Panel concluded that the area that the Project would affect is not a critical part of the range of the George River caribou. Nevertheless, VBNC must carry out its proposed mitigation measures to avoid adverse effects on caribou travelling through the area. If necessary, VBNC might even have to suspend parts of its operations for a short period while caribou are migrating through. Other recommendations include addressing winter shipping concerns through the shipping agreement between LIA and VBNC.

Although VBNC has collected information on numbers of black bears in the area of the Project, there is not enough information to judge the importance of the area in comparison to the rest of the region. The Panel has therefore recommended that the Province carry out further studies. Presenters acknowledged that VBNC had greatly improved its procedures at Voisey's Bay to avoid having to kill "problem" bears, and the Panel has recommended that VBNC develop a special environmental protection plan for black bears.

Birds

The area of northern Labrador that would be affected by the Project, including the shipping route, contains many breeding colonies of seabirds and important habitat for coastal waterfowl. A major oil spill would pose the biggest risk to these birds, although noise could also affect breeding populations. The Panel has recommended emergency response planning to deal with the effects of an accident, an oily waste management plan for VBNC's ships and a monitoring plan to study the effects of noise.

Harlequin ducks breed on several streams in the Project area, including one that flows out of the lakes that would be used for the North Tailings Basin. The eastern population of harlequin duck is listed as an endangered species. VBNC expects the Project to displace between three and six breeding pairs, but predicts that they would quickly move to alternative habitat. The Panel has concluded that the Project would add to cumulative effects on harlequin ducks. The Panel has therefore recommended that VBNC take all possible steps to reduce these effects, and develop a monitoring and research program to better understand the habitat needs of harlequins, including what type of mitigation measures work best. The Panel believes that VBNC, by doing this, could contribute significantly to the success of the National Recovery Plan for harlequin ducks, which would offset the negative effects of the Project.

The Panel heard many concerns about VBNC's decision to locate the airstrip for the Project a few kilometres away from the Gooselands, an important salt marsh habitat and staging area for waterfowl and a valued Aboriginal hunting area. Both government bird experts and Inuit hunters told the Panel that aircraft flying over the Gooselands on approach or takeoff could scare birds, causing them to abandon the area temporarily or, possibly, permanently. The Panel has concluded that the effects of the airstrip on the Gooselands are still uncertain. The Panel has therefore recommended that VBNC either

- realign the runway and delay its plans to operate a Category 1 airport until new aircraft approach technology has been developed; or

- operate with air traffic restrictions that could include restricting flights during critical periods for migratory waterfowl.

Aboriginal Land Use and Historical Resources

Aboriginal presenters told the Panel that they were concerned that the Project could affect both the wildlife and plants that they depend on, and their ability to harvest them. Their concerns included

- loss of habitat;

- disturbance of wildlife;

- possible contamination of country foods;

- additional harvesting pressures from Project employees; and

- reduced access to resources, both at the Project site and through disruption of ice travel.

The Panel has concluded that the Project need not cause widespread harvest disruption if VBNC carried out its mitigation measures carefully. However, the Panel has recommended that VBNC put in place a harvesting compensation program as part of the IBAs. It would also be particularly important that VBNC enforce policies and procedures to prevent employees from fishing or hunting during the two weeks they are working and living at the site.

There are a number of known archaeological and historical resources in the Project area, and more might be discovered during construction. The Panel has recommended that VBNC prepare a revised protection and management plan to ensure that these sites would be properly identified and protected.

Employment and Business

The Project would provide both employment and business opportunities to people living in Labrador and other parts of the province. Following a policy it calls the adjacency principle, VBNC proposes to give first preference to members of LIA and the Innu Nation, then other residents of Labrador, followed by residents of the mainland portion of the province.

Issues brought to the Panel included

- training, and particularly how it can be made relevant and accessible to Aboriginal people and to women;

- ways Aboriginal people can get on-the-job experience;

- the possible impacts of unionization on employment for local people;

- transportation difficulties for people who live in communities south of Rigolet;

- language and cultural issues at the work site, and how these could affect the retention of Aboriginal employees;

- ways to make a mine site a comfortable and supportive place for women employees; and

- problems around access to child care and elder care that could make it difficult for some people, particularly women, to get employment at the Project.

The Panel has concluded that, even with the adjacency principle and VBNC's employment commitments in the IBAs, Aboriginal people in northern Labrador would likely face a number of barriers to employment. Once they were hired, they would also face some major adjustments in getting used to an industrial work site and a fly-in/fly-out rotational work system.

The Panel has made a number of recommendations that address these issues. They include

- improving the existing Multi-Party Training Program to increase access to training for Aboriginal people and for women;

- designating Cartwright as a pick-up point for employees;

- setting up anti-racism and cross-cultural programs;

- implementing a second chance policy for employees who run into difficulties adjusting to their jobs;

- establishing a process to ensure that women's concerns and perspectives are built into all decision making in the workplace; and

- implementing measures to improve child care services in home communities.

VBNC predicts that the Project would deliver approximately one quarter of its total economic benefits to Labrador through business opportunities. The Panel heard concerns about the length of the Project and how that would affect people's decisions to invest in local business development; the availability of information to help business people plan; and VBNC's contract tendering procedures. The Panel has recommended that VBNC develop a comprehensive supplier development strategy to provide timely information and make it easier for local suppliers to put in competitive bids.

Families and Communities

Because the Project would be a fly-in/fly-out operation, with transportation provided to all North Coast communities, Happy Valley-Goose Bay and Labrador West, and because VBNC would give preference to employees living in Labrador, the Project is not expected to create big population changes in any community, with the exception of Nain. Therefore, employment provided by the mine is expected to be the main cause of social changes to families and communities.

Many people told the Panel that they feared the Project would undermine their culture and values, and change their relationship to the land. VBNC predicted that there would be adjustment problems, but that increased employment and income would eventually lead to greater community well-being. Many people challenged this idea, saying that Aboriginal people in particular get their sense of self-esteem from other sources, such as culture, tradition and skills on the land. Some presenters were afraid that the Project would result in more drinking and violence in the home, rather than less. They also pointed out that there could be a greater gap between people who earn good wages at the mine and those who do not.

The Panel also heard from many presenters who wanted to see more economic opportunities for North Coast people and who were looking forward to employment at the Project.

The Panel has concluded that nobody can be totally certain how the Project would affect families and communities because the proposed mine and mill would create such a new situation for northern Labrador. Many other factors would also have an effect, quite apart from the Project. The Panel has also concluded that there is a need for new economic development because, although very important, the harvesting of renewable resources through hunting and fishing cannot adequately support the growing population in the area.

The Panel agrees that, if the Project goes ahead, Aboriginal people must be treated with fairness, justice and respect to avoid negative social effects. To achieve this, all parties should ensure that Aboriginal people received a broad range of benefits through employment, IBAs and reinvestment of the increased revenues that governments would get from the Project. The Panel has recommended that the federal government do this by improving airports in the coastal communities, and that the provincial government put some of the revenues back into improving community-based preventive health care programs.

Because Nain is the closest community to the Project, it would see more direct changes than other communities, relative to its size. Presenters told the Panel that they were concerned about

- the Town's ability to respond to new demands and pressures;

- the effect of the Project on housing and the cost of living;

- the ability of Nain businesses to prepare to bid on contracts; and

- the effect of the Project on existing businesses because of competition for employees or services.

The Panel has recommended that VBNC pay a grant in lieu of taxes to the Town and that the Town and the company set up better communications to deal with problems and opportunities. The Panel has also recommended that the Town, LIA, and the federal and provincial governments prepare a five year housing strategy.

Environmental Management

Throughout the review, many presenters said that if the Project goes ahead, a good environmental management system must be in place. The system would ensure that the effects of the Project were carefully monitored and that VBNC took quick corrective action, if necessary. It would also enable Aboriginal people, throughout the life of the Project, to review and make recommendations on key Project elements, from the start of construction through final decommissioning.

The Panel has recommended a number of steps that should be taken, either in conjunction with the settlement of land claims agreements or as separate but equivalent measures. As one of the first steps, the federal and provincial governments, LIA and the Innu Nation should establish an Environmental Advisory Board with a mandate to review VBNC's monitoring program, permit applications and environmental protection plans. The Board could also address ongoing environmental management issues and concerns. Other recommendations address the need for

- a shipping agreement between VBNC and LIA;

- a broader marine management planning process under the terms of the Oceans Act;

- reclamation objectives that would be incorporated into every aspect of Project planning and operations;

- financial assurances;

- an effective biophysical monitoring program to be carried out by VBNC; and

- a socio-economic monitoring program that would be the responsibility of the Province.

The full Panel report contains more details about all of the Panel's conclusions and recommendations.

The Panel wishes to thank everybody who took part in this environmental assessment review for sharing their knowledge, experience and ideas.

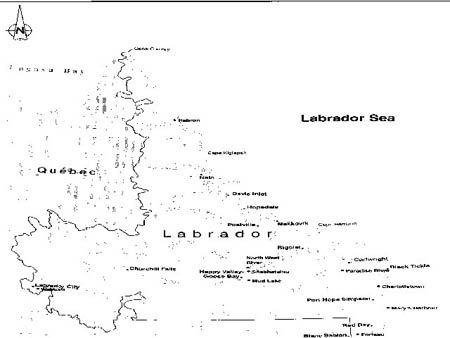

Map of Labrador

1 Introduction

1.1 Memorandum of Understanding

On January 31, 1997, the governments of Canada and Newfoundland and Labrador, and the presidents of the Labrador Inuit Association (LIA) and the Innu Nation, announced the signing of a memorandum of understanding (MOU). Under this MOU, they agreed to establish a joint environmental assessment review of a proposal by the Voisey's Bay Nickel Company (VBNC) to develop a mine and mill near Voisey's Bay, Labrador.

The MOU was established to harmonize the environmental assessment processes of the federal and provincial governments and to recognize the interests of the two Aboriginal groups who have overlapping land claims in the area.

With a membership of about 5,200, the Labrador Inuit Association represents both Inuit and "Kablunangajuit" - an Inuktitut term for the people of northern Labrador who are also referred to as "Settlers." LIA members reside primarily in Nain, Hopedale, Makkovik, Postville, Rigolet, North West River and the Upper Lake Melville area. For the purposes of this report "Inuit" is used to describe LIA members. The Innu Nation represents approximately 1,500 Innu mainly living in the communities of Sheshatshiu and Utshimassits (Davis Inlet). A map of Labrador communities appears on the opposite page.

The Department of Fisheries and Oceans has federal responsibility for the review process because of its responsibility to issue an authorization for destruction of fish habitat under subsection 35(2) of the Fisheries Act and a permit under section 5 of the Navigable Waters Protection Act. In order to participate in the harmonized review process, the provincial government exempted the project from the Newfoundland Environmental Assessment Act.

A complete copy of the MOU can be found in Appendix C. It includes direction on administering the process and important definitions relating to the environmental assessment process. Schedule 1 to the MOU contains the terms of reference for the review, outlines the review's scope and timelines, and lists factors to be considered during the review. Figure 1 summarizes the review process.

Figure 1: Steps in the Panel Review Process

- Signing of the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), appointment of the Panel, Terms of Reference released - January 31, 1997

- Operational Procedures issued by the Panel - March 12, 1997

- Draft Guidelines for the Preparation of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) issued by the Panel - March 14, 1997

- Scoping meetings - April 16 - May 26, 1997

- Panel issued Final Guidelines for the Preparation of an EIS - June 20, 1997

- EIS submitted and 75-day review period commenced - December 17, 1997

- Announcement of a 30-day extension for the review period of the EIS - February 20, 1998

- End of the EIS review period - March 31, 1998

- Request for Additional Information released by the Panel - May 1, 1998

- Start of the 45-day review period of the Additional Information - June 1, 1998

- Panel determined that sufficient information was provided to proceed to public hearings - July 30, 1998

- Schedule for public hearings and Hearing Procedures issued - August 6, 1998

- Public hearings - September 9 - November 6, 1998

- Panel Report Sent to MOU Parties - March 1999

1.2 Panel History and Membership

The independent Joint Panel on the Voisey's Bay Mine and Mill Development Proposal was appointed on January 31, 1997 to conduct the public review of the undertaking. It includes Ms. Lesley Griffiths (Chair), Mr. Samuel Metcalfe, Ms. Lorraine Michael, Dr. Peter Usher and Dr. Charles Pelley, whose biographies appear in Appendix A.

1.3 Participant Funding

The Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (CEAA) made funding available to help interested groups participate in the review process. A funding committee, independent of the Panel and administered by CEAA, assessed the applications and awarded a total of $150,000 to 12 groups for the first phase of the review process, which included scoping of the environmental assessment. For the second phase of the review process, which included public hearings, the committee awarded $259,000 to 13 groups. The public was encouraged to participate throughout the process, which included preparing the final guidelines for the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), and reviewing the adequacy of the EIS and Additional Information.

1.4 Review Process

Following the panel's appointment on January 31, 1997, draft EIS guidelines were issued on March 14, 1997 for public review and comment. The guidelines outlined the issues that VBNC was asked to respond to in its EIS. Public meetings were held in April and May 1997 to allow interested organizations, groups and individuals to inform the Panel of the range of issues they thought the Panel should address during the review. These "scoping sessions" were held in Nain, Rigolet, Hopedale, Postville, Makkovik, Sheshatshiu and Utshimassits, as required by the MOU. Given the interest shown by other communities, the Panel also held scoping sessions in Goose Bay, Cartwright and St. John's. After carefully considering the comments received, the Panel released the final EIS guidelines on June 20, 1997.

On December 17, 1997, VBNC's response to the guidelines, the EIS, was released for the 75-day public comment period required under the MOU. The Panel added 30 days to the review period after VBNC released some background documents to the EIS. The Panel reviewed the EIS, and considered comments on the document's adequacy submitted by members of the public, environmental groups, community organizations, Aboriginal groups, and federal and provincial government departments and agencies. On May 1, 1997, following this process, the Panel requested more details from VBNC in a number of areas where the EIS did not provide sufficient information to support meaningful discussion at public hearings. These details (known as Additional Information) were provided to the Panel on June 1, 1998 and then made available for a 45-day public review period, as required by the MOU.

On July 30, 1998, the Panel announced its determination that the EIS, background documents and the Additional Information contained sufficient detail to support meaningful discussion of the proposal at public hearings.

The public hearings allowed individuals, organizations and government representatives to provide their views on the implications of the proposed project. VBNC was also allowed to explain the project and respond to concerns and questions raised by other participants. Between September 9 and November 6, 1998, the Panel held 32 days of hearings in Nain, Utshimassits, Sheshatshiu, Hopedale, Rigolet, Postville and Makkovik. Hearings were also held in Goose Bay, Cartwright, Labrador City, and St. John's. The public hearings included community, general and technical sessions. A list of sessions can be found in Appendix D.

This report is the final stage of the process to be completed by the Panel. It summarizes the concerns the Panel heard, the Panel's findings, and the conclusions and recommendations the Panel is making to provincial ministers, federal ministers, and the presidents of LIA and the Innu Nation.

A public registry of all documents, including submissions made to the Panel during the scoping meetings and public hearings, was maintained at the Panel's office in Nain and at the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency in Hull, Quebec.

1.5 Project Description

Over the course of the environmental assessment review process, elements of the proposal have evolved. While the Panel sees no significant change in the original project description in the MOU, it recognizes that the Project will continue to evolve. The Panel considered this fact when reaching its conclusions and determining its recommendations for this report. The description that follows is consistent with the Project description provided by VBNC in its EIS and the Project description that accompanied the MOU.

VBNC proposes to develop a nickel-copper-cobalt mine and mill near a place known to the Inuit of Labrador as Tasiujatsoak and to the Innu of Labrador as Kapukuanipant-kauashat, which is also known as Voisey's Bay. The proposed mine and mill would be located in northern Labrador, 35 km southwest of Nain and 79 km northwest of Utshimassits.

The indicated mineral resource is estimated to be 150 million tonnes and consists of three ore bodies, described by VBNC as the Ovoid, the Eastern Deeps and the Western Extension. VBNC proposes to mine 32 million tonnes of ore from the Ovoid using conventional open pit techniques, and to mine the anticipated 118 million tonnes of mineral resource from the Western Extension and Eastern Deeps using underground techniques. The Eastern Deeps and Western Extension zones will require further exploration before the details of a mine plan can be determined. At full capacity, the mill would process ore into nickel-cobalt and copper concentrates at a rate of 20,000 tonnes of ore per day. Concentrates would be trucked to storage facilities at the port site at Edward's Cove and shipped off site for further processing.

Site infrastructure would include a plant, a port facility and storage area at Edward's Cove, access roads, accommodations and an airport. See page 4 for a map of the site.

The site map also shows the Landscape Region of 20,000 km² identified by VBNC as the geographic basis for VBNC's assessment of terrestrial, aquatic, and marine ecosystems potentially affected by the Project.

VBNC's preferred shipping route extends from Edward's Cove to the east end of Paul's Island and then passes north of the Hens and Chickens. VBNC prefers to ship using an extended shipping season. This would entail no shipping during the period of initial ice formation and during early spring.

During mining and concentrating operations, the Project would produce mine rock and tailings that could generate acid. There is a proposal to place these materials under a permanent water cover to inhibit acid generation. Mine rock and tailings would be co-disposed in Headwater Pond during open pit mining, which is expected to last for the first eight years that the mine operates. During underground mining, tailings would be placed in the North Tailings Basin, located about 10 km northeast of the plant site, and acid generating mine rock would continue to be placed in Headwater Pond. Waste rock that did not generate acid would be stored in surface facilities.

Another important part of the project description is the water management plan, which encompasses all stages of the mine operation. The key objectives of this plan are to reduce environmental effects on freshwater and marine habitats, to use as much reclaimed water from within the water management system as possible and to recycle water within the mill as much as possible.

Upon closure, the project site would be decommissioned and reclaimed to return it to a safe and environmentally stable condition.

Direct on-site employment would peak at approximately 950 during the underground phase. During operations, VBNC proposes transporting workers to the project by aircraft from pick-up points in local communities. Living accommodations would be provided on site for workers as no town site is planned.

2 The Project and Sustainable Development

2.1 Context

To ensure the effects of the Project were properly assessed, the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) specifically instructed the Panel

- to consider the need for the Project;

- to address the Project's effects on biological diversity, and on the capacity of renewable resources to meet the needs of present and future generations; and

- to examine the extent to which VBNC applied the precautionary principle to the Project.

The Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (the CEA Act) defines sustainable development as "development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs." In the guidelines, the Panel interpreted the three objectives of sustainable development as follows, and indicated that these interpretations would guide its review of the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) and other submissions:

- the preservation of ecosystem integrity and maintenance of biological diversity;

- respect for the right of future generations to the sustainable use of renewable resources; and

- the attainment of durable and equitable social and economic benefits.

The Whitehorse Mining Accord looked at the implications of sustainable development for mineral resource extraction and used a multi-stakeholder approach to develop a strategic approach to sustainability in mining. Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) further developed these issues and included the objective that "the economic and social benefits of mineral development are not all consumed by the present generation and that current investment in human and physical capital benefit future as well as present generations."

In the EIS, VBNC committed to extract minerals and metal products efficiently at all stages of mining and processing, in order to reduce environmental effects and improve economic benefits, and to respect the needs and values of other resource users throughout the life of the Project.

Many submissions to the Panel addressed various aspects of sustainability that are discussed throughout this report. This chapter describes how the Panel reached an overall conclusion about the Project in the context of sustainable development.

2.2 Ecosystem Integrity, Biodiversity and Renewable Resources

The Panel asked VBNC to describe how the Project would extract the mineral resource at Voisey's Bay without impairing ecosystem integrity or biodiversity, and how it planned to protect the plant and wildlife resources that Aboriginal people have used for generations and that continue to form a vital part of their local economy, and social and spiritual well-being.

VBNC acknowledged the ecological values and sensitivities of the Landscape Region in which the Project would be located, especially those associated with Reid Brook, the Gooselands and the marine resources of the five-bay complex. It also acknowledged the significance of the landfast sea ice as habitat and as an extension of the land for the purposes of local travel and harvesting. VBNC indicated that the design and operation of the Project would

- minimize the land-based footprint of the Project and, hence, the amount of disturbance to terrestrial habitat;

- prevent direct Project discharges into the Reid Brook system or the Voisey's Bay estuary;

- prevent acidification of streams and lakes and subsequent mobilization of metals into the food chain by storing sulphide-rich tailings and waste rock permanently under water;

- minimize effects on wildlife through employee policies and training and various forms of mitigation; and

- reduce the effects of shipping on landfast ice by limiting winter shipping and through other forms of mitigation.

Many presenters told the Panel that, to protect the environment and the resources that support Aboriginal harvesters and their families, VBNC must pay meticulous attention to dust control; water, tailings and waste rock management; and protection of habitat for plants, fish and wildlife. In every North Coast community, people expressed great concern about the effects of winter shipping on landfast ice, and Inuit in particular also questioned the effects of the airstrip on the Gooselands. The Panel addresses all of these issues in chapters 5 through 13.

The Panel concludes that, in many respects, the Project is a relatively conventional mining operation using proven mitigation measures, and that its effects can be predicted with reasonable certainty. However, the Panel recognizes that the Project must deal with a number of significant challenges, including

- the protection of the Reid Brook system, given the location of the open pit and other Project features;

- the protection of the Gooselands and the waterfowl that use this salt marsh;

- safe navigation through ice and the complex pattern of islands, headlands and shoals;

- the protection of sea ice users during VBNC shipping through landfast ice; and

- effective reclamation in a subarctic environment.

The Panel concludes that VBNC could construct, operate and decommission the Project without either significantly damaging local and regional ecosystem functions, or reducing the capacity of renewable resources to support present and future generations. To do so, VBNC must operate within an effective environmental management system, as the EIS proposes; implement further mitigation, as this report recommends; and use the results of a scientifically sound effects monitoring program to improve environmental performance throughout the life of the Project.

However, the Panel believes that sufficient uncertainty remains about the effects of shipping through landfast ice that this component of the Project should not proceed until these questions have been resolved to the satisfaction of the Labrador Inuit Association (LIA) and government.

The Panel also concludes that effective environmental management of the Project would require, not only diligent efforts by VBNC, but also the continued cooperation of the four parties to the MOU and the development of an environmental co-management organizational structure in northern Labrador, such as that described in Chapter 17.

2.3 Durable and Equitable Social and Economic Benefits

The Panel asked VBNC to indicate how the Project would deliver durable and equitable social and economic benefits to Aboriginal people in northern Labrador, other Labrador residents and the province. VBNC stated that the Project would, over a period of 20 to 25 years, deliver these benefits in three ways:

- direct employment at the Project and related business opportunities, targeted to LIA and Innu Nation members and the rest of Labrador through the application of a company policy called the adjacency principle;

- financial participation in the Project by LIA and the Innu Nation through impact and benefit agreements (IBAs); and

- increased government taxation revenues.

Many individuals and organizations told the Panel that the Project could indeed deliver benefits, provided some crucial conditions were met. First and foremost of these was that the Project should, as proposed, last 20 to 25 years and preferably more. This would enable workers to earn pensions and accumulate savings beyond one generation, and to develop industrial and business skills that could support new economic activities. At the same time, communities could use the increased flow of income over a long period to diversify their local economies. A long duration would also reduce the risk of negative effects associated with the community boom-and-bust effect.

The Panel, and many presenters, while recognizing VBNC's intentions to develop both the open pit and underground phases of the Project, observed that two major uncertainties might affect Project life - volatile nickel prices and incomplete knowledge about the extent of the underground reserves. The Panel addresses these issues in Chapter 3, Project Need and Resource Stewardship. It concludes that, despite these uncertainties, the Project could deliver durable benefits, if VBNC is required to carry out the planned underground exploration program and to adapt production rates as necessary to ensure that the mineral resource is extracted over a period of at least 25 years.

Many presenters also told the Panel that a second crucial condition would be that VBNC deliver employment and business benefits to Innu and Inuit communities as promised, and that the fly-in/fly-out operation not become, in fact, a "fly-over" operation. VBNC and others should also ensure that both men and women benefit. The Panel addresses these issues mainly in Chapter 15, Employment and Business, and concludes that Inuit and Innu and other Labradorians would benefit from Project-related employment and business, provided that IBAs were finalized and implemented. VBNC must also ensure appropriate training (in cooperation with other parties), consistent application of the adjacency principle, and close attention to language, cultural and gender-based aspects of working conditions.

VBNC acknowledged that individuals and communities in northern Labrador would experience some negative social and economic effects and that the Project might increase economic disparity. VBNC sees these effects as mostly short term, as communities go through a period of adjustment, and indicated that long-term improvements in individual and community health and well-being would more than offset them. The Panel heard many views and concerns about these issues, which it addresses mainly in Chapter 16, Family and Community Life, and Public Services.

The Panel concludes that this is a complex issue, that the Project would cause both negative and positive social effects, and that these effects would not be distributed equally. The Panel also concludes, however, that an economy based only on harvesting renewable resources is unlikely to be capable of sustaining the growing Innu and Inuit populations, and that social and economic change is both inevitable and ongoing. The Panel believes that the Project could deliver significant positive social effects and that negative effects would be manageable if IBAs were successfully negotiated and implemented, and increased government revenues were reinvested in regional services and infrastructure. As discussed in Chapter 4, the Panel also believes that land claims agreements - or equivalent binding measures dealing with Project consultation, compensation and participation - must be in place before the Project starts to ensure Inuit and Innu can more effectively control their lives and futures.

2.4 Precautionary Principle

The MOU instructed the Panel to consider the extent of the precautionary principle's application to the Project. The Rio Declaration of 1992, to which Canada is a signatory, states that the precautionary approach requires that "where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation." The CEA Act provides no guidance on the application of the precautionary principle to environmental assessment.

In determining whether Project-environment interactions could lead to serious or irreversible damage, the Panel considered

- the degree of novelty of the interaction in similar environments;

- the degree of uncertainty about potential effects;

- the magnitude and duration of potential effects and the extent to which they might be irreversible; and

- the extent and scale at which potential effects could impair biological productivity and ecosystem health.

The Panel considers that the precautionary principle or approach requires a proponent to demonstrate that its actions will not result in serious or irreversible damage. Specifically, the Panel asked VBNC to show that it had

- designed the Project to avoid adverse effects wherever possible;

- developed mitigation measures, or contingency or emergency response plans, of proven effectiveness;

- designed monitoring programs to ensure rapid response and correction when adverse effects are detected (or would design these in cooperation with others, where appropriate); and

- developed adequate systems to remediate any residual accidental or unplanned adverse effects of the Project and demonstrated sufficient financial resources to compensate for such effects.

The Panel asked VBNC to take a conservative approach to its predictions by, for example, using worst case scenarios, where appropriate. The Panel sought assurance that, if there was great uncertainty about the seriousness and irreversibility of the effects of any Project component, that VBNC could reduce this uncertainty, correct the problem or suggest a viable alternative to that component.

VBNC stated that, in its view, the precautionary principle as applied to the Project means anticipation and prevention, so designers and planners should incorporate environmental information into all stages of their activities. VBNC advised the Panel of the ways in which it had incorporated the precautionary principle into the Project's design to prevent adverse effects, prevent pollution, deal with unplanned events, develop monitoring and follow-up programs, and ensure that the company's liability and insurance regime holds it accountable for damages. The Panel examines these claims in detail in the appropriate chapters.

The Innu Nation and LIA recommended more restrictive interpretations of the precautionary principle. For example, one expert appearing on behalf of the Innu Nation suggested that the principle requires the Panel to begin with the hypothesis that the Project would damage the environment, and to reject that hypothesis only under the weight of contrary evidence. The Innu Nation also stated that any action with long-term or irreversible consequences precludes some future options, which is contrary to the principle of sustainability. It asserted that adaptive management relies on a monitoring and mitigation approach, which would violate both the precautionary and sustainability principles. The Innu Nation expressed the precautionary principle simply as "if we wait and see, it will be too late."

The Panel concludes that it was not presented with plausible hypotheses, well grounded in experience and theory, that the Project, or key elements of it, would cause serious or irreversible adverse environmental effects. The Panel also concludes that any uncertainties about these matters could be satisfactorily addressed by the measures recommended in this report.

2.5 Aboriginal Knowledge

The MOU instructed the Panel to "give full consideration to traditional ecological knowledge whether presented orally or in writing." The Panel provided guidance on this requirement in its guidelines by characterizing traditional ecological knowledge as a subset of Aboriginal knowledge. It defined the latter as "the knowledge, understanding, and values held by Aboriginal people that bear on the impacts of the Undertaking and their mitigation," based on "personal observation, collective experience, and oral transmission over generations." The Panel further noted that Aboriginal knowledge is evolving with new experience and understanding, so it did not wish to limit Aboriginal people's contribution to the assessment to what is commonly known as traditional ecological knowledge.

Those elements of Aboriginal knowledge relating to values, norms and priorities were particularly important in the scoping phase of the review and strongly informed the Panel's guidelines. The guidelines indicated that Aboriginal knowledge relating to such matters as ecosystem function, resource abundance, resource distribution and quality, land and resource use, and social and economic well-being would be essential when developing baselines, predicting impacts and assessing the significance of effects in the EIS and during the public review.

The Panel indicated that VBNC should either obtain this information with the cooperation of other parties and present it in the EIS, or help Aboriginal persons and parties present such information directly to the Panel during the review.

In 1995, VBNC entered into discussions with LIA and the Innu Nation to obtain Aboriginal knowledge for its EIS. During the next three years, it funded workshops, reports and studies. The results of these activities were, for the most part, presented directly to the Panel by LIA and the Innu Nation, rather than in the company's EIS. The aboriginal organizations presented issues scoping reports; reports on land use, environmental knowledge and potential environmental effects; and, in the case of the Innu Nation, a report on socio-economic conditions and a video showing current Innu family and community conditions and describing personal perspectives on the Innu future. The Panel understands that VBNC did not influence, or seek to influence, the content or quality of the projects it funded.

The Panel considers that VBNC adequately conformed to the guidelines and commends its efforts in a situation where guidance and experience are lacking. When Aboriginal knowledge was presented in technical hearings, the Panel considered it on the same basis as other expert information, keeping in mind that the hearings were conducted in a non-judicial, non-adversarial fashion. The Panel considers that Aboriginal knowledge was used effectively during the review, both in the technical and the community hearings.

Conclusion

Based on the foregoing conclusions, the Panel believes that the Project could contribute significantly to sustainable social and economic development on the North Coast and in the rest of Labrador, without harming vital ecosystem functions and habitats or the ability of Inuit and Innu to keep using land in traditional ways. To make this contribution, VBNC must uphold the commitments it made during the review process and work diligently throughout the life of the Project to prevent or minimize adverse effects and maximize benefits. The Panel also believes that each of the four parties to the MOU would have a continuing and essential role to play to ensure progress towards environmental and community sustainability.

Recommendation 1

The Panel recommends that the Voisey's Bay Mine and Mill Project be authorized to proceed, subject to the terms and conditions identified in the rest of the Panel's recommendations.

3 Project Need and Resource Stewardship

3.1 Project Need and Timing

In its guidelines, the Panel directed the proponent to justify the need for the Project. VBNC responded in the EIS and hearings by describing what it saw as a growing market for nickel, the weak state of the provincial and regional economies, and the economic viability and potential of the Project. VBNC stated that it wished to develop the project "to meet Inco's strategy of developing low-cost nickel deposits and remaining as the world's leading producer of nickel."

For many presenters, the question of need was most closely tied to timing. In other words, does the project need to start immediately, or can it be delayed by a number of years? Some people suggested that delaying the project could make the project more economically viable, which would in turn enhance local benefits and ensure high enough returns to adequately cover the costs of environmental protection and reclamation. A second argument made in favour of delay was that it would reduce potential adverse social impacts by giving Aboriginal people and communities time to prepare. Aspects of viability are addressed in this chapter. Aspects of readiness are addressed in chapters 15, 16 and 17.

The Panel believes that the exact definition of "need" for a new mining venture is somewhat problematic. It considers the following factors possible components of project justification:

- the global economy's need for new nickel and for the benefits that nickel products provide (copper and cobalt are seen as by-products and secondary to this discussion);

- the need to build and maintain low-cost reserves for the Canadian nickel industry in order to support both the industrial needs of VBNC's parent company, Inco, and continued Canadian economic activity; and

- the requirement for regional economic development based on producing primary metal.

Some presenters urged the Panel to look not only at the demand side (world nickel markets) but also at the supply side when reviewing the requirement for new nickel. They wanted to ensure that nickel reserves were conserved for the use of future generations and to reduce the overall environmental impacts related to the extraction, use and disposal of materials.

3.1.1 Materials Consumption and Environmental Consequences

Nickel is a non-renewable resource. However, the main argument that the Panel heard in favour of slowing the extraction of this finite commodity related not to a fear that the world would run out of nickel but to a concern that global ecosystems cannot afford the environmental consequences of the current throughput of industrial materials, let alone an expansion.

An ecological economist speaking on behalf of the Innu Nation argued that the Western world probably needs to reduce the total throughput of materials by 75 percent. This would, he said, reduce the accumulating levels of environmental stress and degradation that result from all phases of materials use, while accommodating the basic needs of less developed countries. While not arguing to cancel the Voisey's Bay Project, he did suggest that delaying its start and reducing its scale would contribute significantly to environmentally responsible supply management. He argued that the Project can only be justified by a societal need for goods and services based on the "virgin" metals produced by the Project. Then he provided a list of factors to be considered, based on existing and potential mines, existing and projected consumption, potential substitution of other metals for nickel and recycling rates.

The Innu Nation also argued that high grade deposits, not just low grade deposits, should be left for future generations and that excess supply is a disincentive to developing more efficient product uses.

Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) told the Panel that approximately one third of the nickel used in stainless steel is recycled metal. It was NRCan's position that metals are not destroyed but are "placed in inventory on surface." The Panel observes that this would tend to support the argument that high grade deposits should be mined first. An expert, appearing on behalf of the Innu Nation, agreed with this premise to a certain extent by arguing that, since low grade deposits are energy and pollutant intensive, and since extractive technology will change, it may make sense to exploit high grade deposits first, thus causing less environmental damage and building up the recycling inventory.

The Panel agrees that conservation of materials, including nickel, is an important objective. During the hearings, the Panel heard about the high levels of recycling achieved in the nickel industry. It is also aware that Inco is developing new uses for nickel that should increase the value of the product without necessarily increasing the amount used. The Panel does not believe, however, that an environmental assessment of one project can satisfactorily address issues of global nickel use and conservation. The Panel suspects that nickel not supplied by VBNC would quickly be supplied by another producer. This might cause more environmental damage and provide fewer benefits than the VBNC Project, particularly if mining occurred without the constraints imposed on a Canadian project.

The Innu Nation also discussed the rate at which a finite resource such as nickel should be extracted from the ground to ensure durable and equitable benefits. The following sections address production rates and resource stewardship.

3.1.2 World Nickel Markets

The main fact VBNC used to justify the need for the Project is that the nickel market has grown by a compounded 4 percent since 1963. Other participants pointed out that the annual compound growth rate is overestimated because the growth rate was 6.5 percent from 1960-73 but only 1 percent from 1973-96. They also observed that the growth rate is bound to drop as the market increases in size.

The nickel consumption graph shown in Figure 2 shows that there was almost no growth between 1984-92 and renewed high growth in the past few years. This corresponds to the primary nickel demand described in the Additional Information, which states that demand has recently increased by approximately 50,000 tonnes per year, from 769,000 tonnes in 1993 to 1,004,000 tonnes in 1997. The annual consumption increase is therefore quite variable, depending on the period chosen.

Looking at projected consumption growth without relying on historical growth projections seems to be difficult. An NRCan expert said that production figures are considered more accurate than consumption figures because actual consumption is difficult to measure accurately. For instance, the consumption of nickel in stainless steel is tracked to the point of steel production, as opposed to final consumption. However, VBNC noted that demand for nickel in superalloys grew at the rate of 8 percent per annum between 1993 and 1997. This suggests the emergence of a market not reflected in past consumption data. This market may partially support the strong growth seen in recent years.

Annual per capita consumption figures from NRCan show a world demand of 1.9 kg, with very high consumption in steel producing countries such as Taiwan, South Korea and Japan. Consumption in less developed populous regions is low. For example, China consumes 0.6 kg, India 0.7 kg, Africa 0.4 kg and Eastern Europe 0.6 kg. However, consumption in those regions is increasing rapidly.

The other important market force is supply. With the exception of Raglan, most of the new capacity outlined by both the Innu Nation and NRCan will come from nickel laterites. These deposits require extracting metals from oxide ores using leaching processes similar to those that have proven successful in low grade copper and gold ores. The largest of these new projects is Murrin Murrin in Australia, which, if its second stage expansion occurs, would be the same size as Voisey's Bay. However, NRCan indicated that both recovery rates and financing for this project were uncertain. Both Inco and Falconbridge have also announced pilot projects to extract lateritic ores in New Caledonia, and Cuba also has large lateritic reserves.

Another important source of supply is Russia. That country has the world's largest sulphide reserves at Norilsk and exports large quantities of stainless steel scrap from dismantled military infrastructure.

Innu Nation experts based their analysis on the assumption that the project would add to existing productive capacity. The Panel notes, however, that Inco has already announced that it will reduce high cost production in its Ontario and Manitoba divisions, as discussed in more detail later in this document. Other sulphide based producers around the world are experiencing difficulties at present prices. Botswana production, for example, is very heavily subsidized at present prices and nickel concentrates have been imported to keep the smelting operation viable.

The Panel concludes that there is a high degree of uncertainty in projections of market growth. For example, the period required for growth to absorb the projected capacity of Voisey's Bay during Ovoid production ranges from about 3 to 17 years, depending on the assumptions used. Per capita consumption figures suggest both that growth potential is high and that it is tied significantly to emerging economies. The present slump in nickel prices with the slowing of the Asian economies also supports that conclusion.

On the supply side, the Panel recognizes the uncertainty of the supply of recycled stainless steel coming from the former Soviet republics. In addition, the supply of lateritic nickel may be significant but the cost efficiency of the related extraction process is uncertain.

Figure 2 - Global Consumption of Nickel

3.1.3 Importance to the Canadian Economy

The Panel does not consider the review to be a proper forum for discussing the importance of the Project to the economic viability of Inco. However, the Panel acknowledges the contribution of the nickel industry to the Canadian economy. Inco is the largest producer in the Canadian nickel sector, which had net export earnings of $1.6 billion in 1997. Inco accounts for over 70 percent of the capacity of the three Canadian smelters and over 80 percent of the capacity of the three Canadian refineries. Most of the concentrates for the three Canadian smelters are produced locally in Thompson and Sudbury, while Falconbridge augments its smelter feed from the Raglan mine in northern Quebec. The two Sudbury smelters have undergone major capital upgrades and have potential for significant future operating life.

The supply of cost-effective Canadian concentrates is being threatened. In Sudbury, Inco's near-surface reserves are low grade; the higher grade material is located at depths below 2000 m. Falconbridge is short of reserves in Sudbury and is relying on Raglan and other exploration properties to augment its supply. There is exploration potential in Labrador (the Kiglapaits and Donner Resources sites), a significant exploration program in northeastern Quebec near Sept-Iles and a recently announced discovery in northern Quebec. At present, there are no known offshore sulphide deposits that can supply significant quantities of concentrates to Canadian smelters, and there are no known major commitments to look for such deposits. Therefore, Canada must manage and develop its supply.

The Panel believes there is some justification for concerns that structural change in the nickel market may reduce long-term prices. It is also difficult to assess the sustainability of Russia's present level of exports of primary metal and stainless steel scrap, or the potential success of methods for extracting oxide nickel from laterites. Even with these uncertainties, VBNC is willing to make a major investment based on the Ovoid reserves and believes that, with extraction facilities in place, it can profitably extract a significant portion of the underground resources.

The Panel observes that there is potential for growth in the world nickel market and that new domestic sources will have to be developed just to maintain Canada's existing position. Given that Inco supplies about 20 percent of that market, the Panel assumes that Inco, as part of its internal justification of the project, will assure itself that production from Voisey's Bay is required. In addition, Inco will have to convince financiers that its projections are valid before development proceeds.

3.1.4 Need for Local Economic Development

While it was made quite clear to the Panel that economic development at any cost was not an option, people in Aboriginal communities felt that new economic activity was important to the future, provided the environmental effects, the timing and the level of control were satisfactory. In all of the Inuit communities people expressed interest in the direct and indirect jobs that might accrue from the Project. In the Innu communities, elders and younger people indicated that jobs could provide some benefits, including resources to support important traditional activities.

The Panel acknowledges, however, that some Aboriginal people feel they cannot support the Project under any circumstances, because of its social and environmental consequences, and because they feel that a mining project is not compatible with Aboriginal culture, ways of life and aspirations for the future.

In Nain, the Panel heard from a group of presenters who described a busy local economy, with good prospects in fisheries, small-scale quarrying, tourism and crafts. The presenters felt that the Inuit communities had a range of economic development opportunities and need not depend on large resource extraction developments such as the project.

The business community of Happy Valley-Goose Bay strongly supported the Project as a way to diversify the economy away from dependence on the military presence. In Labrador West, already an experienced mining community, people also strongly supported the Project. Chapter 15 discusses regional economic benefits in more detail.

3.2 Production Rate and Mine Life

Throughout the hearings, the Panel heard concerns about the length of the Project from Aboriginal organizations, the Province and many individuals. VBNC is proposing a 25 year project at Voisey's Bay but presenters were concerned that changing circumstances, such as nickel prices, the economic fortunes of VBNC's parent company or poor results from the underground exploration program, could alter this intention. One of the key factors determining the length of the Project (the mine life) is the rates at which VBNC will extract and process the nickel (the production rates).

3.2.1 Proposed Production Rates