Route 389 Improvement Project Between Fire Lake and Fermont

Document Reference Number: 17

Comprehensive Study Report

September 2018

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, (September, 4th, 2018).

Catalogue No: En106-211/2018F-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-27155-2

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial purposes, and in any format, without charge or further permission. Unless otherwise specified, you may not reproduce materials, in whole or in part, for the purpose of commercial redistribution without prior written permission from the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0H3 or info@ceaa-acee.gc.ca

This document has been issued in French under the title: Projet d'amélioration de la route 389 entre Fire Lake et Fermont - Rapport d'étude approfondie préliminaire

Executive Summary

The Quebec Ministère des Transports, de la Mobilité durable et de l'Électrification des transports (the proponent) is proposing a road improvement project (the project) on Route 389 between Fire Lake and Fermont to improve traffic flow and safety, enhance the link with Newfoundland and Labrador, and facilitate access to natural resources. The work includes 55.8 km of alignment on new rights-of-way and the upgrading of the existing road, for a total length of 68.9 km.

Under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (S.C. 1992, c. 37) (the former Act), a federal environmental assessment is required since Fisheries and Oceans Canada will likely need to issue an authorization as part of the project, in accordance with the Fisheries Act, to allow for activities that result in serious harm to fish. Infrastructure Canada could also provide funding to the proponent for this project. The project is subject to a comprehensive study–type environmental assessment because it involves an activity described in section 29(b)Footnote 1 of the Schedule of the Comprehensive Study List Regulations. The Canadian Environmental Assessment, 2012 (the Act), came into force on July 6, 2012, replacing the former Act. In accordance with the transition provisions of the Act, the comprehensive study for the project was completed under the former Act.

The Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (the Agency) prepared the comprehensive study in collaboration with the Federal Environmental Assessment Committee composed of representatives of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Infrastructure Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada, and Health Canada.

In this comprehensive study report, the Agency describes the project's effects on the following valued components: the atmospheric environment, wetlands and plant species with special status, fish and fish habitat, birds and bird habitat, terrestrial wildlife and wildlife habitat, and the current use of lands and resources for traditional purposes.

The Agency assessed the significance of the effects of the project based on information provided by the proponent in its environmental impact statement and supplementary documents, opinions provided by federal and provincial experts, and comments received from the public and First Nations.

The First Nations raised concerns about maintaining traditional activities, access to their traditional territory and its availability to non-Indigenous people, the preservation of the Innu archaeological and cultural heritage, the effects on the sacred Moisie River, the economic opportunities related to the project, and the effects on wildlife, particularly boreal caribou. The summary of concerns raised by First Nations can be found in Appendix G.

The proponent committed to implementing mitigation measures deemed necessary by the Federal Environmental Assessment Committee and that are expected to reduce the potential environmental effects of the project. The measures include a dust management plan, work restrictions during sensitive periods for wildlife and fish habitat compensation measures. The proponent also committed to implementing a follow-up program for a number of valued components and an emergency response plan for accidents and malfunctions.

A follow-up program is required to verify the accuracy of the environmental assessment and to determine the effectiveness of the proposed mitigation measures. Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Infrastructure Canada, as responsible authorities for the project, will be responsible for ensuring the development and implementation of the federal follow-up program.

Taking into account the implementation of the proposed mitigation measures and follow-up program, the Agency finds that the project is not likely to cause significant adverse environmental effects.

The Minister of Environment and Climate Change will consider this report and the comments from the public and First Nations before issuing an environmental assessment decision statement. The minister will then send the project to Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Infrastructure Canada as the responsible authorities to render their decision, in accordance with section 37 of the former Act.

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Project Overview

- 3 Purpose of and Need for the Project, Project Alternatives, and Alternative Means Analysis

- 4 Consultation Activities and Advice Received

- 5 Geographical Setting

- 6 Predicted Effects on Valued Components

- 7 Other Effects Considered

- 8 Potential Impacts on Potential or Established Aboriginal or Treaty rights

- 8.1 Potential or Established Aboriginal or Treaty Rights in the Project Area

- 8.2 Assessment of the Potential Impacts on Aboriginal Rights

- 8.3 Issues to be Addressed During the Regulatory Approval Phase

- 8.4 Agency's Conclusions Regarding Adverse Impacts on Potential or Established Aboriginal or Treaty Rights

- 9 Follow-up Program

- 10 Conclusions and Recommendations of the Agency

- 11 References

- 12 Appendices

- Appendix A: Spatial Boundaries and Rationale

- Appendix B: Mitigation Measures

- Appendix C: Summary of the Federal and Provincial Regulatory Framework for Valued Components in the Environmental Assessment

- Appendix D: Evaluation Criteria for Assessing Environmental Effects

- Appendix E: Grid for Evaluating the Significance of Environmental Effects

- Appendix F: Summary of Potential Residual Effect on Valued Components

- Appendix G: Summary of the Concerns Raised by First Nations

- Appendix H: Criteria and Sub-Criteria for Analyzing Alternatives

- Appendix I: Summarized Performance of Project Alternatives

- Appendix J: Alternative Means Criteria Compared with the Chosen Option

- Appendix K: Projects and Activities Considered in the Cumulative Effects Assessment

List of Tables

- Table 1: Valued components selected by the Agency

- Table 2: Project activities

- Table 3: Options ranked according to the results of the proponent's multi-criteria analysis

- Table 4: Variant assessment criteria

- Table 5: Results of sampling at the Labrador City station, 2014

- Table 6: Area of existing and affected wetlands by the road and the borrow pits

- Table 7: Loss of fish habitat: Summary

- Table 8: Area of existing forest stands and wetlands affected by the road and the borrow pits

- Table 9: Estimated number of pairs of land birds that will be affected by wetland losses during the construction phase of Route 389

- Table 10: Biophysical attributes of critical woodland caribou habitat in the Boreal Shield Ecozone (east)

- Table 11: Area of suitable woodland caribou habitat affected by the road footprint and the area beyond it, during the different life cycle stages

- Table 12: Summary of direct impacts for boreal caribou in the roadway footprint

- Table 13: Scope of the cumulative effects assessment

- Table 14: Disturbance levels of boreal caribou habitat within the area used by local populations considering a 500 m functional impact around anthropogenic disturbances

- Table 15: Area affected by current and future projects in the territory defined for the assessment of cumulative effects on the use of land by Innu First Nations.

- Table 16: Elements of the federal follow-up program

List of Figures

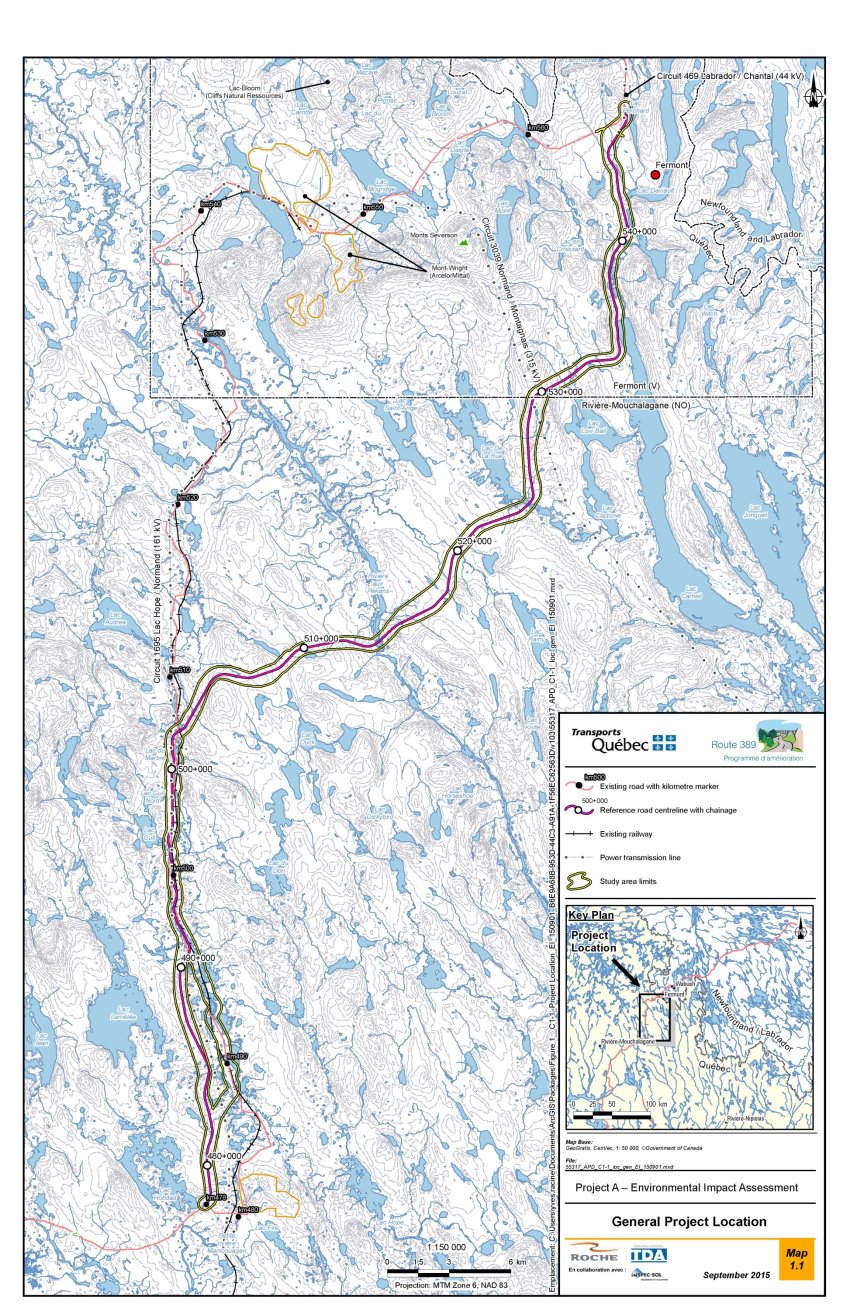

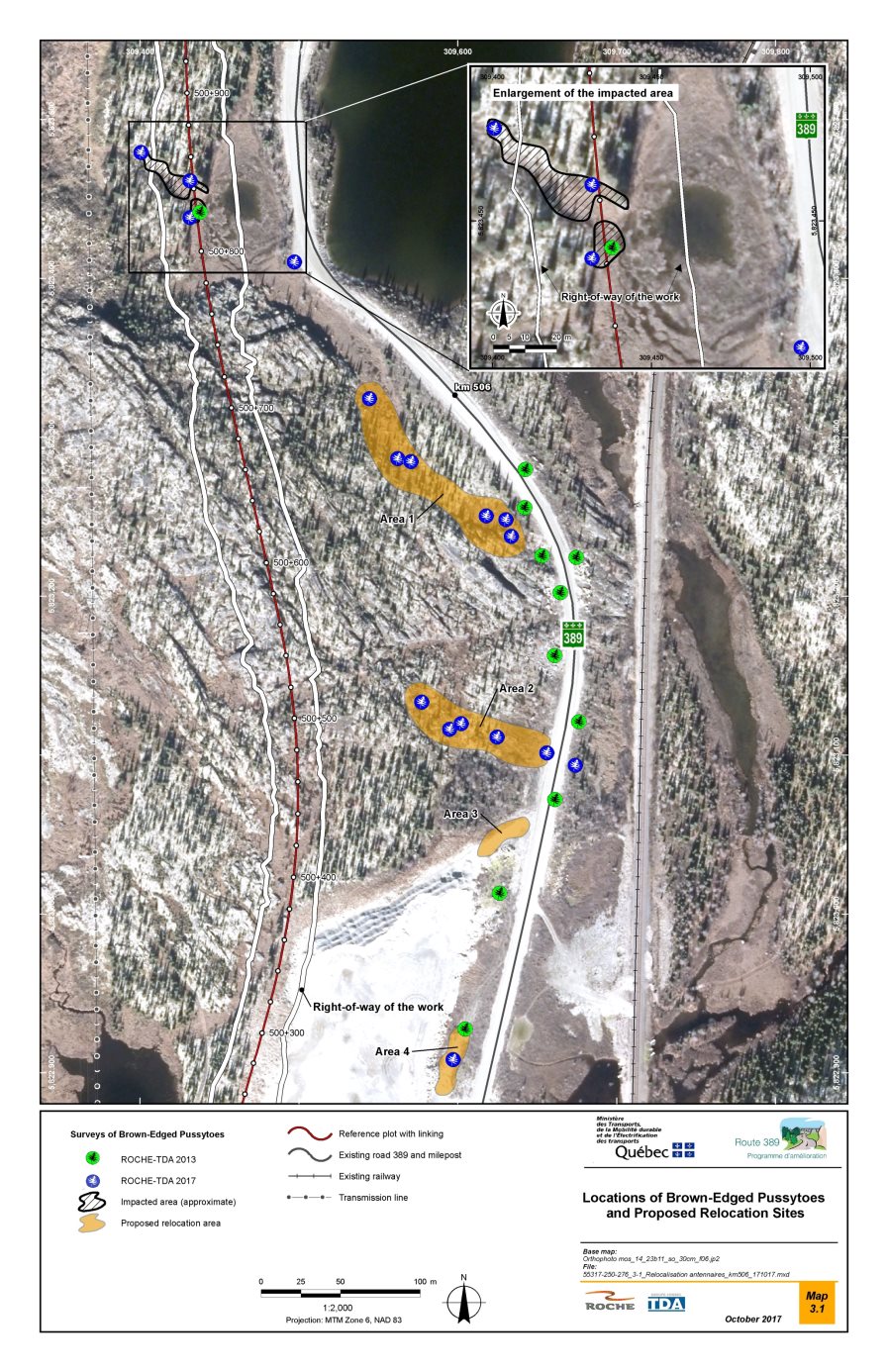

- Figure 1: Project location

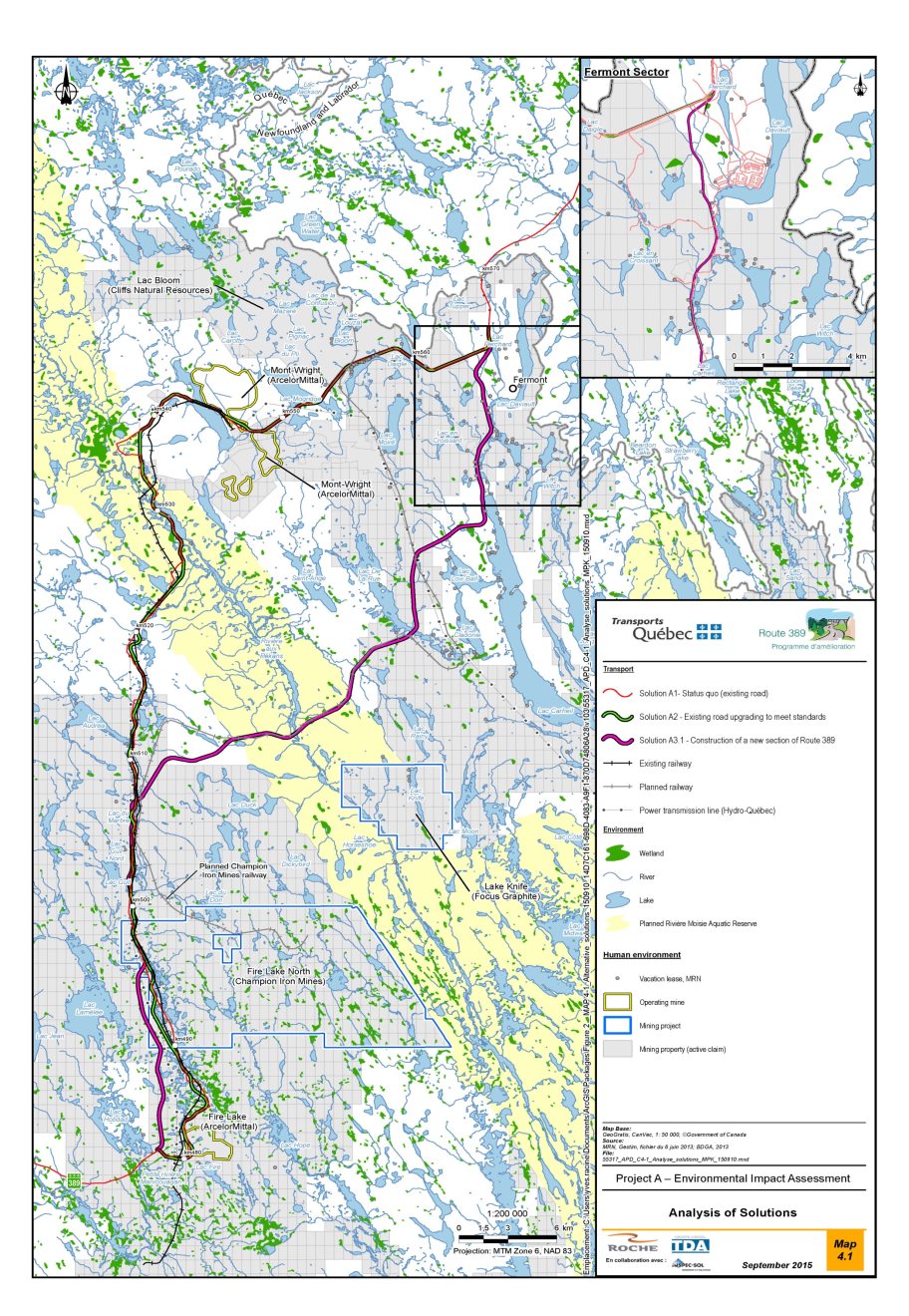

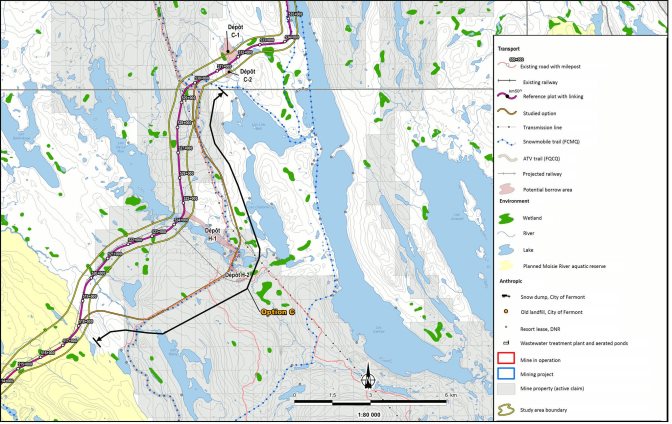

- Figure 2: Project alternatives analyzed by the proponent

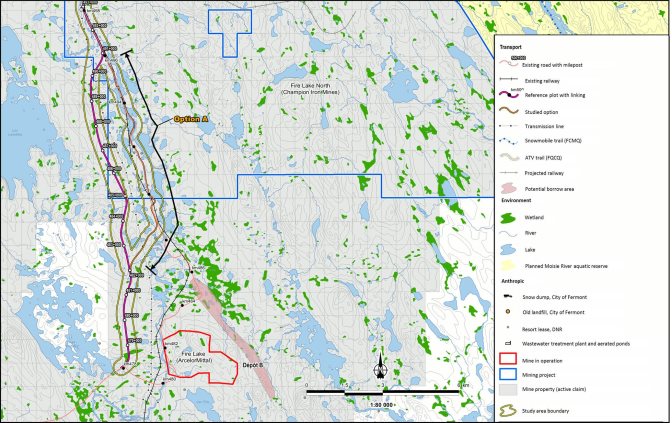

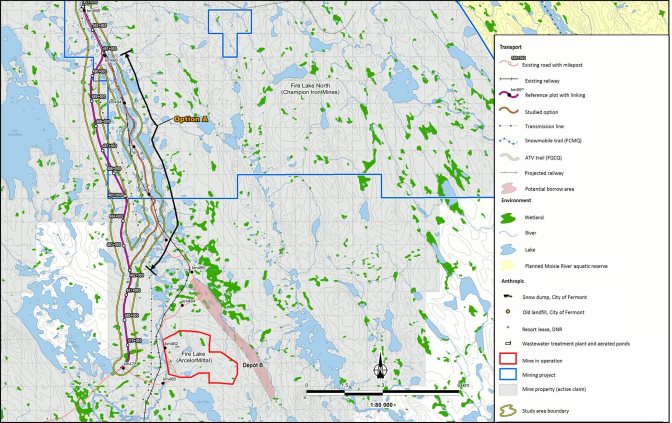

- Figure 3: Map of Variant A

- Figure 4: Map of Variant B

- Figure 5: Map of Variant C

- Figure 6: Map of Variant D

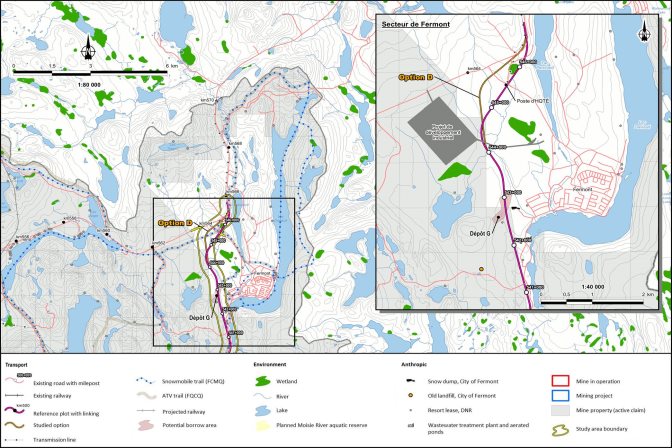

- Figure 7: Map of the planned Moisie River aquatic reserve

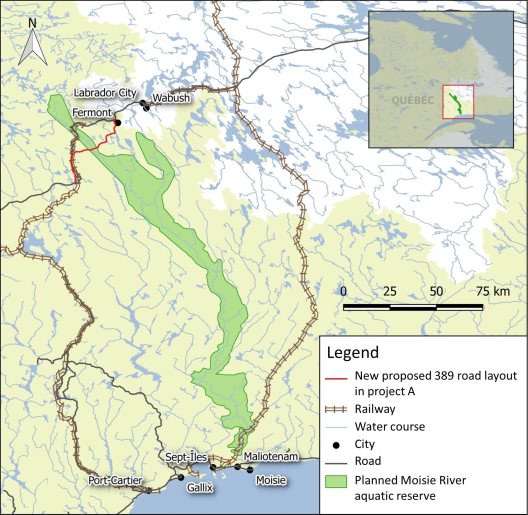

- Figure 8: Locations of brown-edged pussytoes and proposed relocation sites

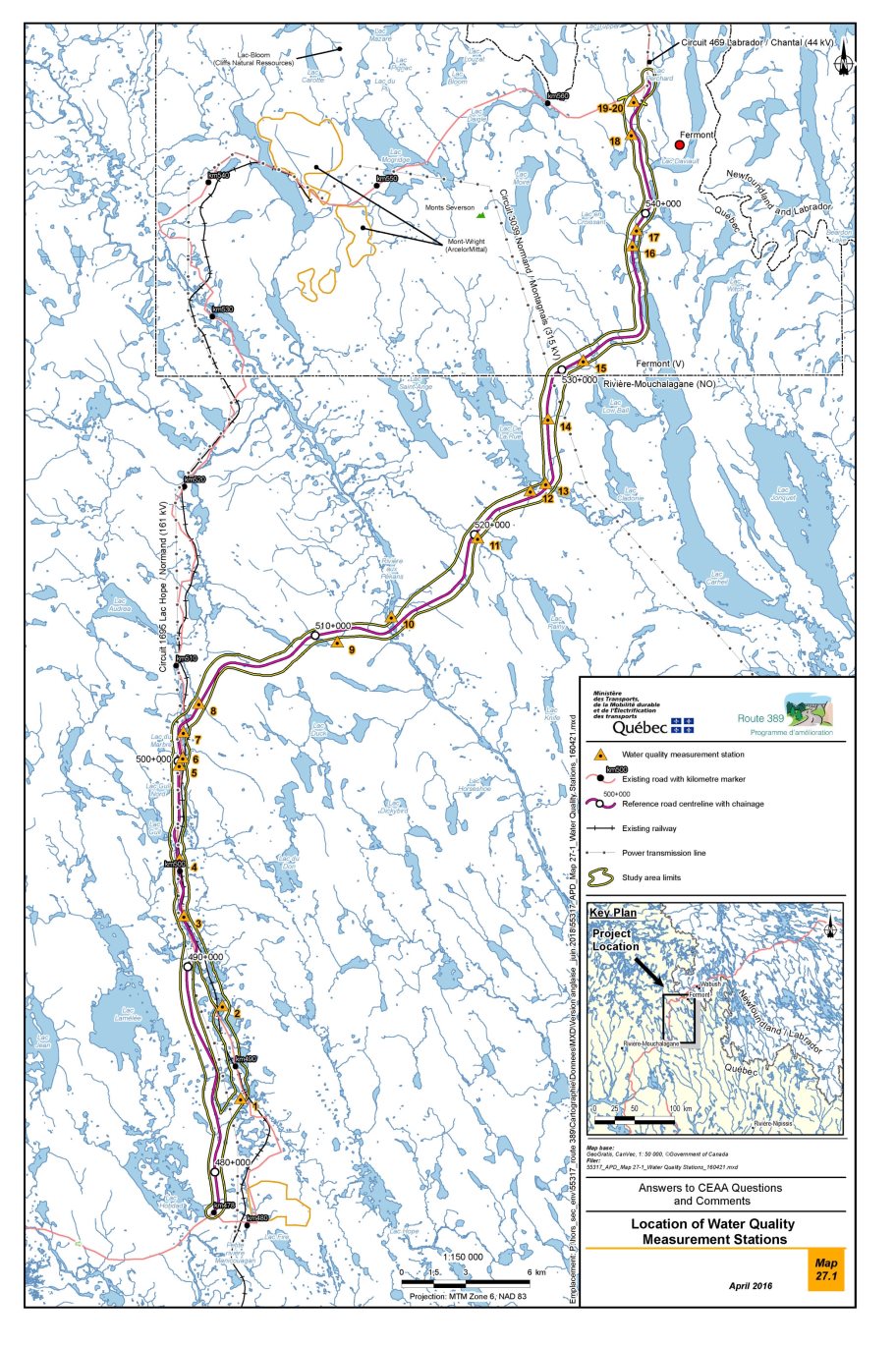

- Figure 9: Locations of water quality monitoring stations

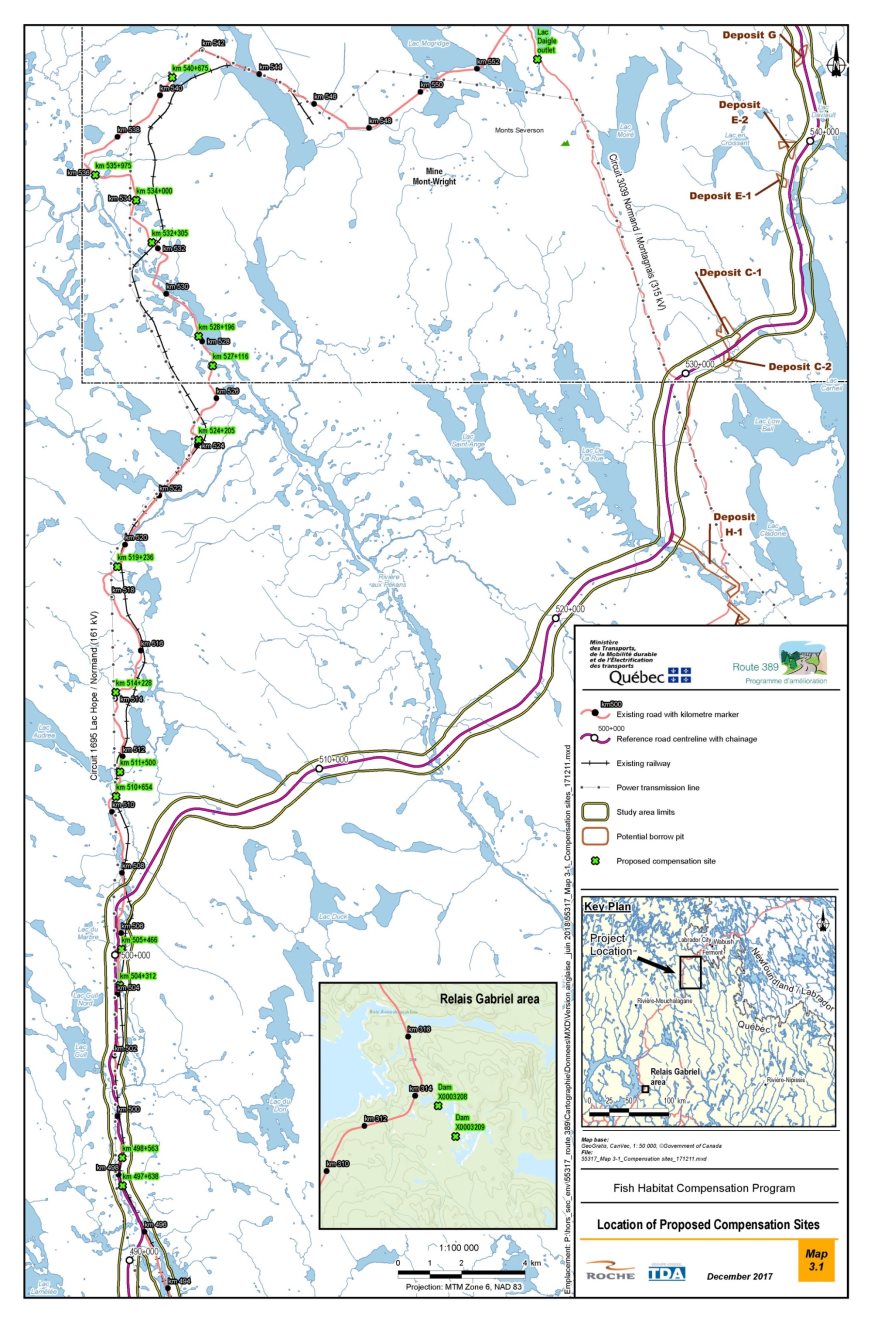

- Figure 10: Location of sites proposed by the proponent where the free passage of fish could be restored to offset serious damage to fish

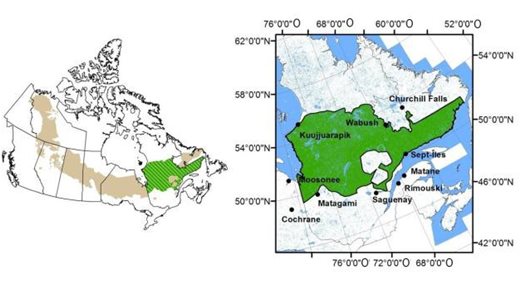

- Figure 11: Woodland Caribou QC-6 Range, Boreal Population Identified in the Woodland Caribou Recovery Strategy (Rangifer tarandus caribou), Boreal Population, Canada

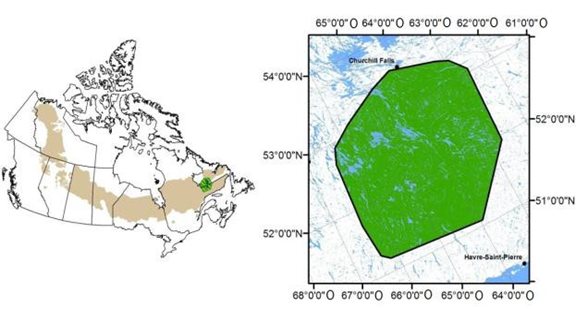

- Figure 12: Woodland Caribou NL-1 Range, Boreal Population Identified in the Woodland Caribou Recovery Strategy (Rangifer tarandus caribou), Boreal Population, Canada

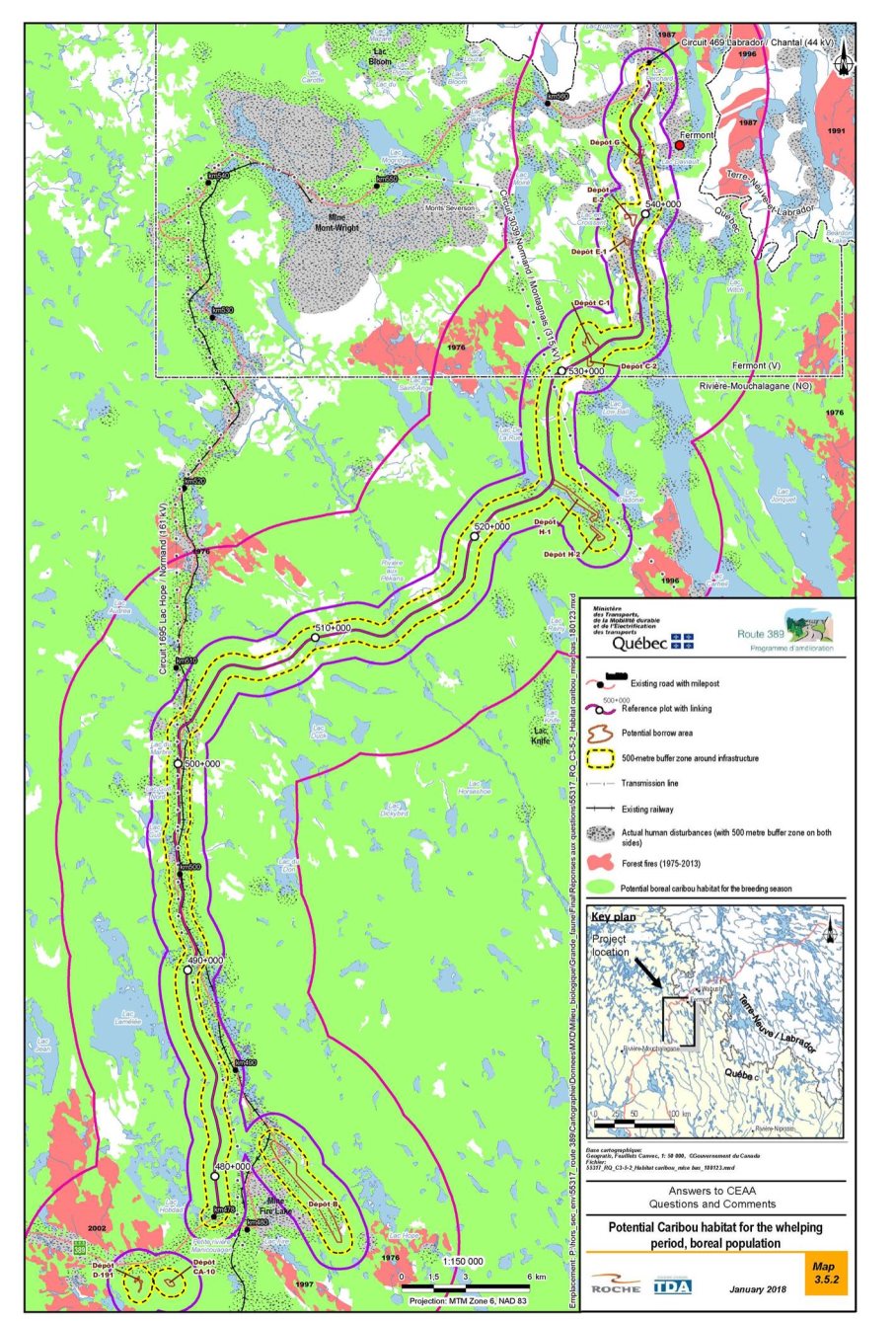

- Figure 13: Potential Boreal Caribou habitat for the calving (whelping) period

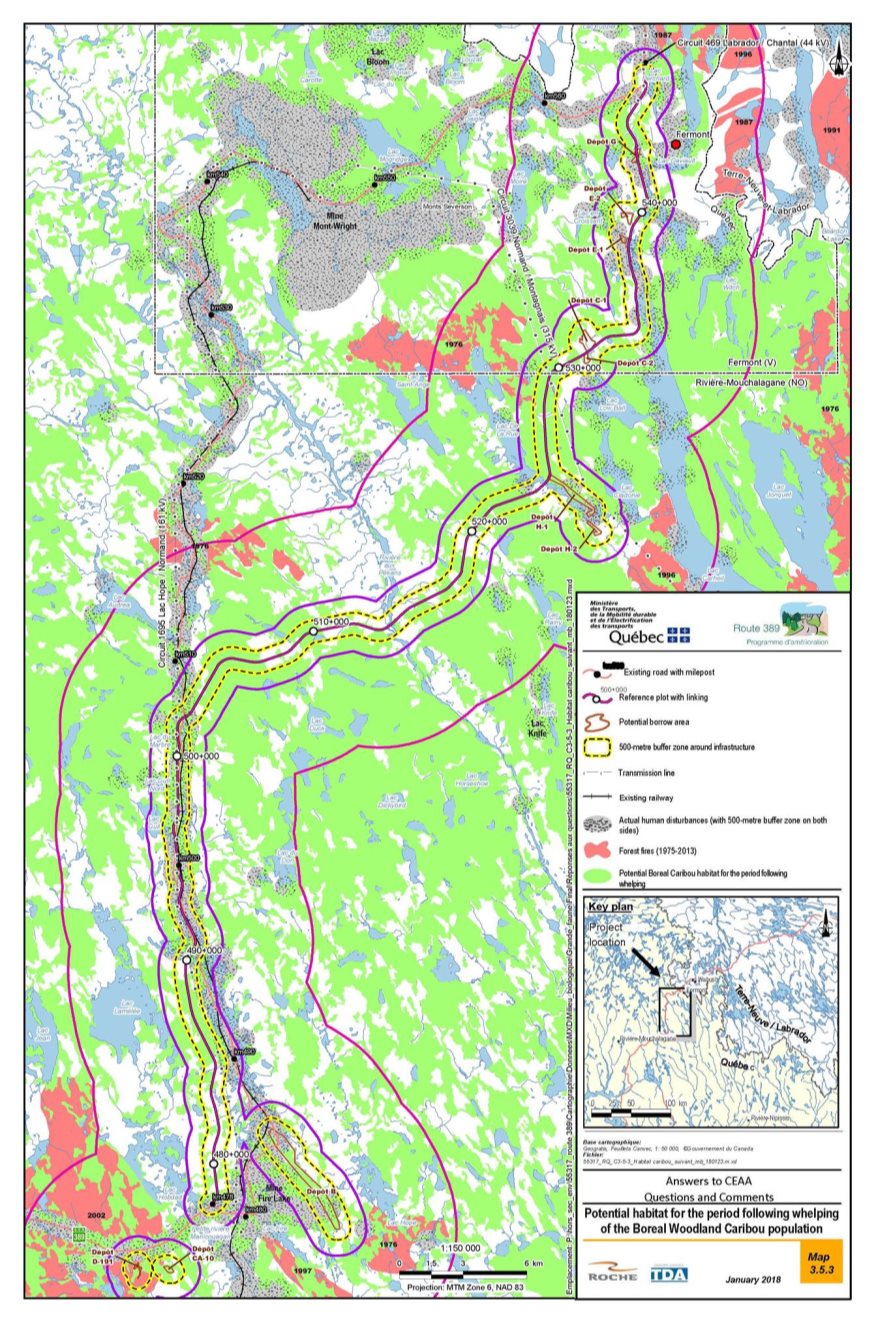

- Figure 14: Potential Boreal Caribou habitat for the post-calving (post-whelping) period

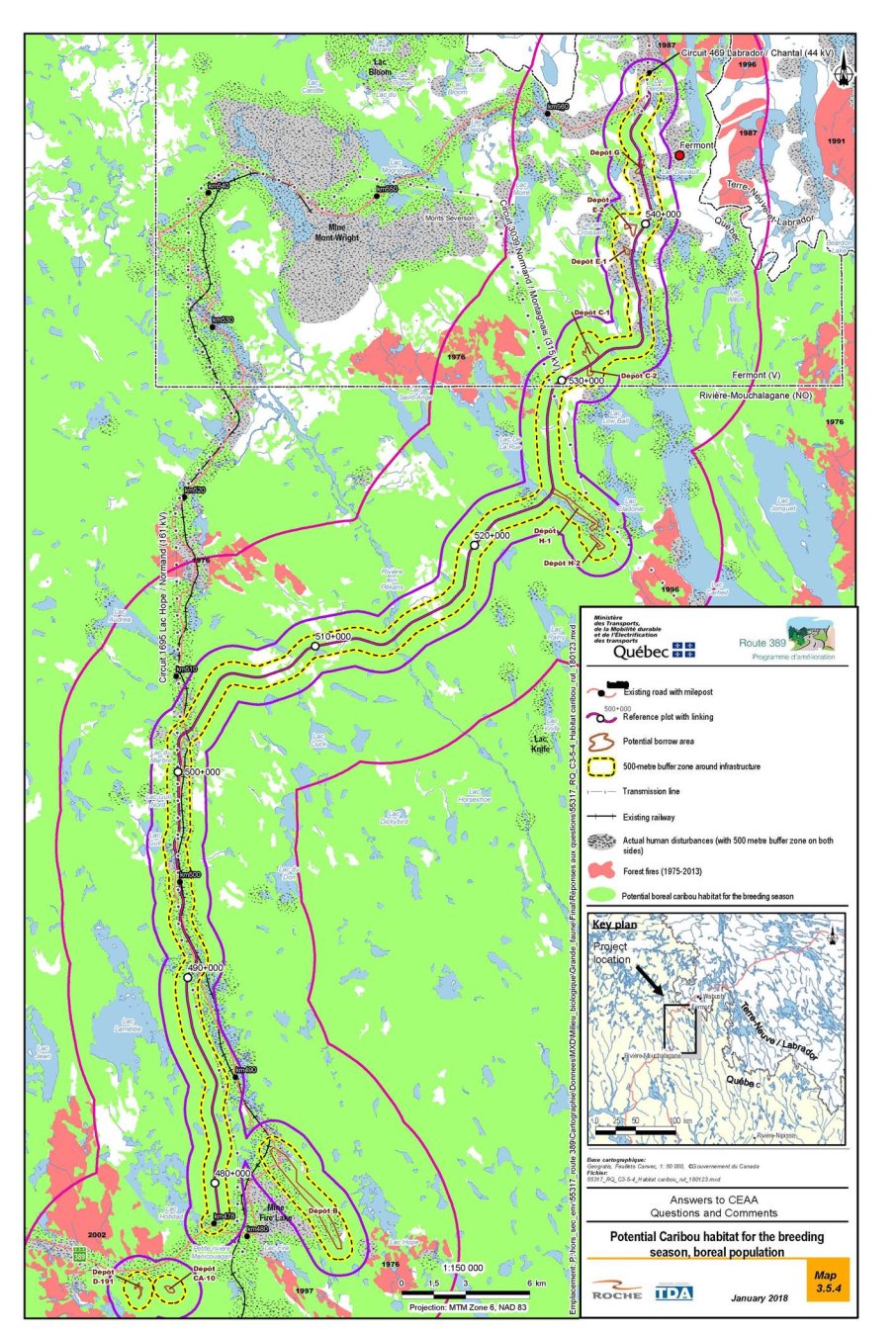

- Figure 15: Potential Boreal Caribou habitat for the rutting (breeding) season

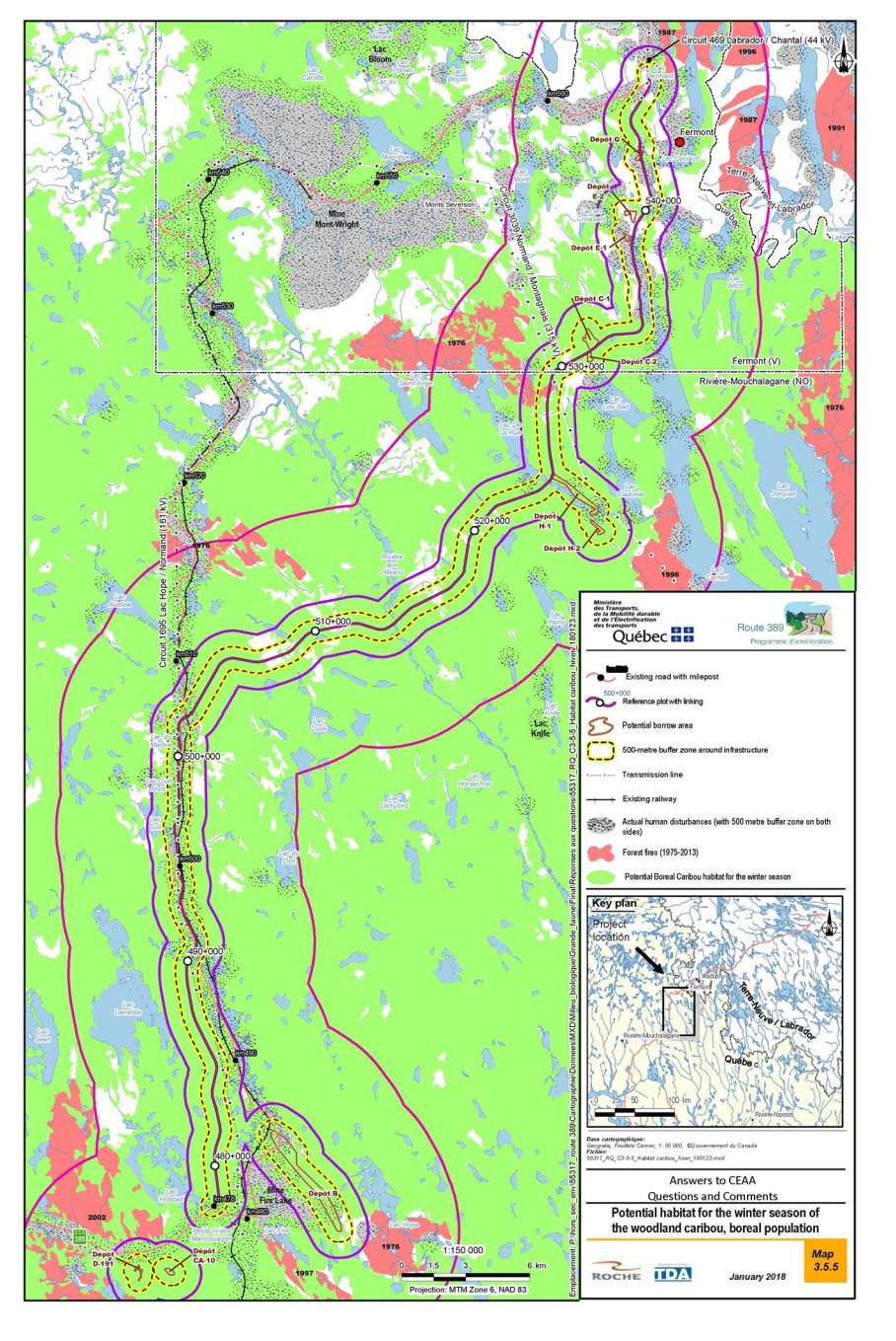

- Figure 16: Potential Boreal Caribou habitat for wintering

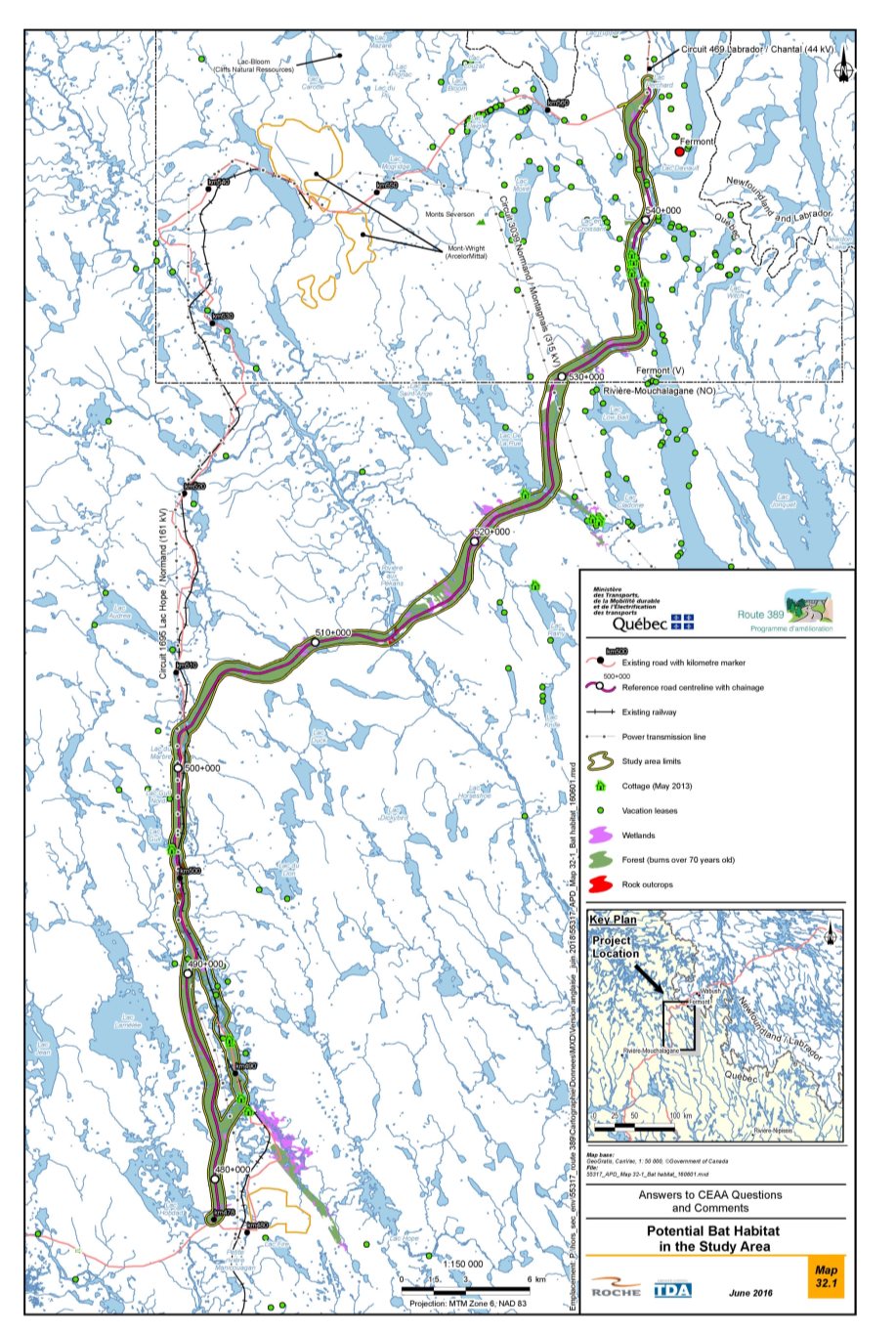

- Figure 17: Potential bat habitat in the study area

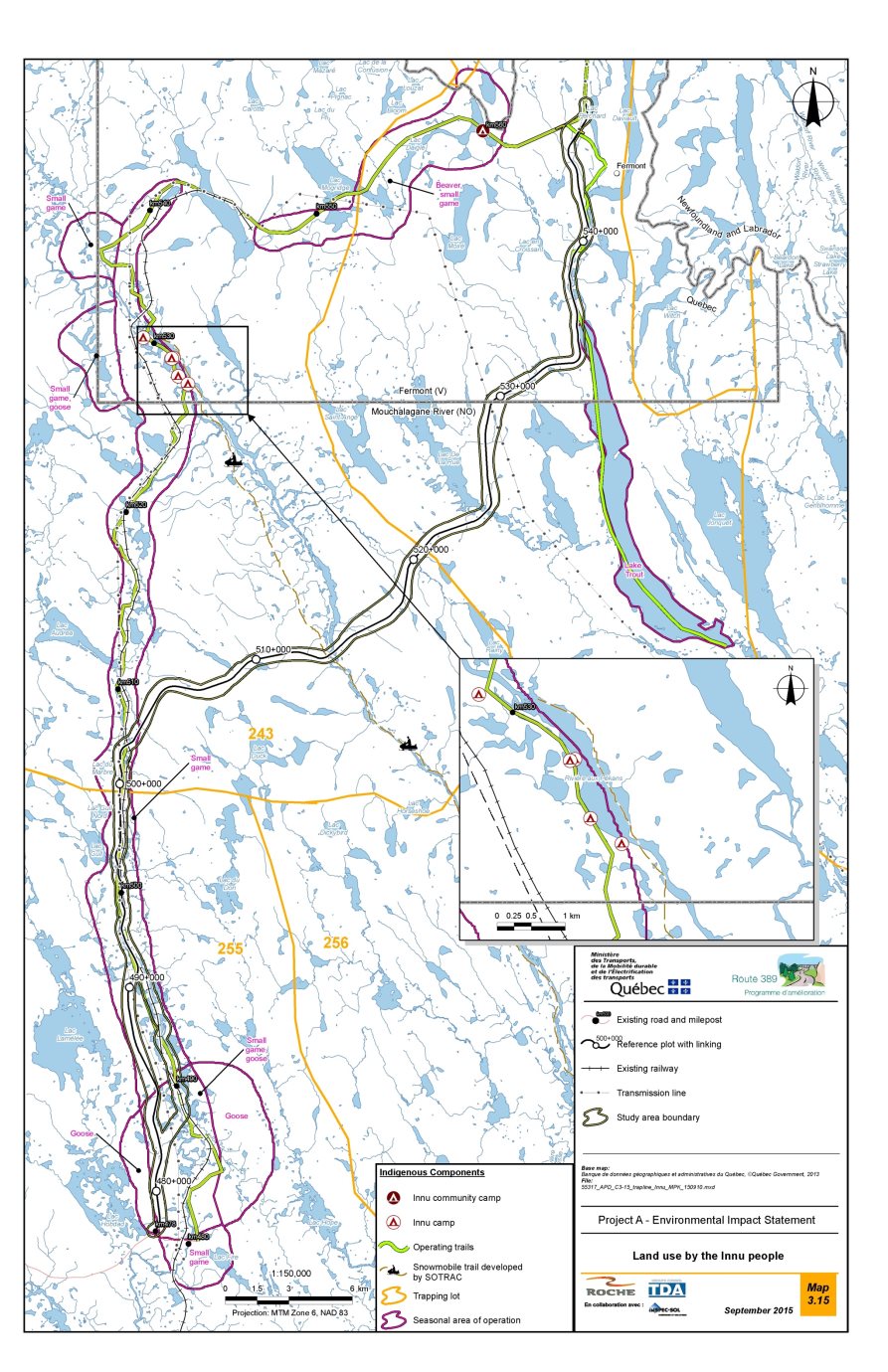

- Figure 18: Use of the territory by the Innu

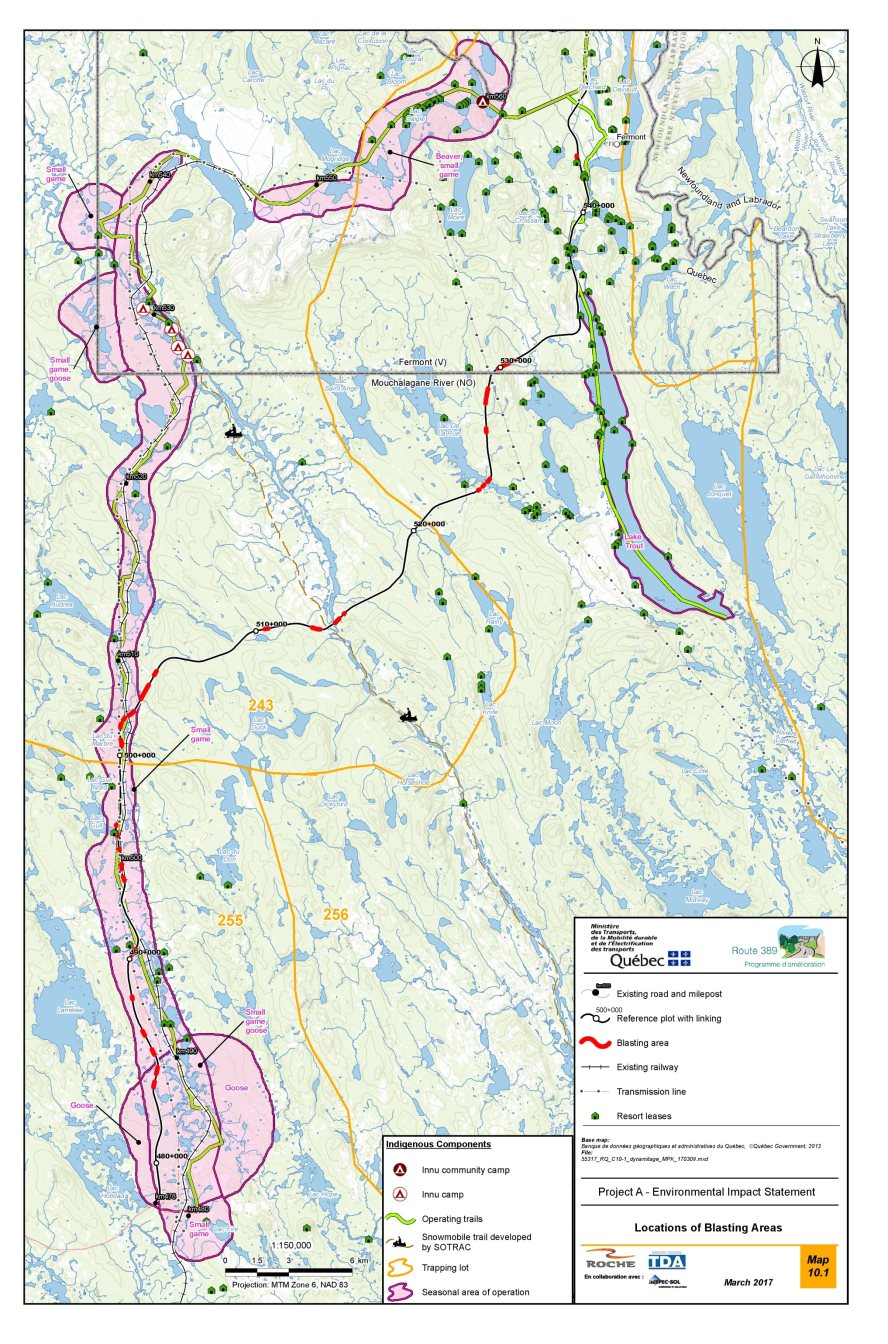

- Figure 19: Locations of Blasting Area

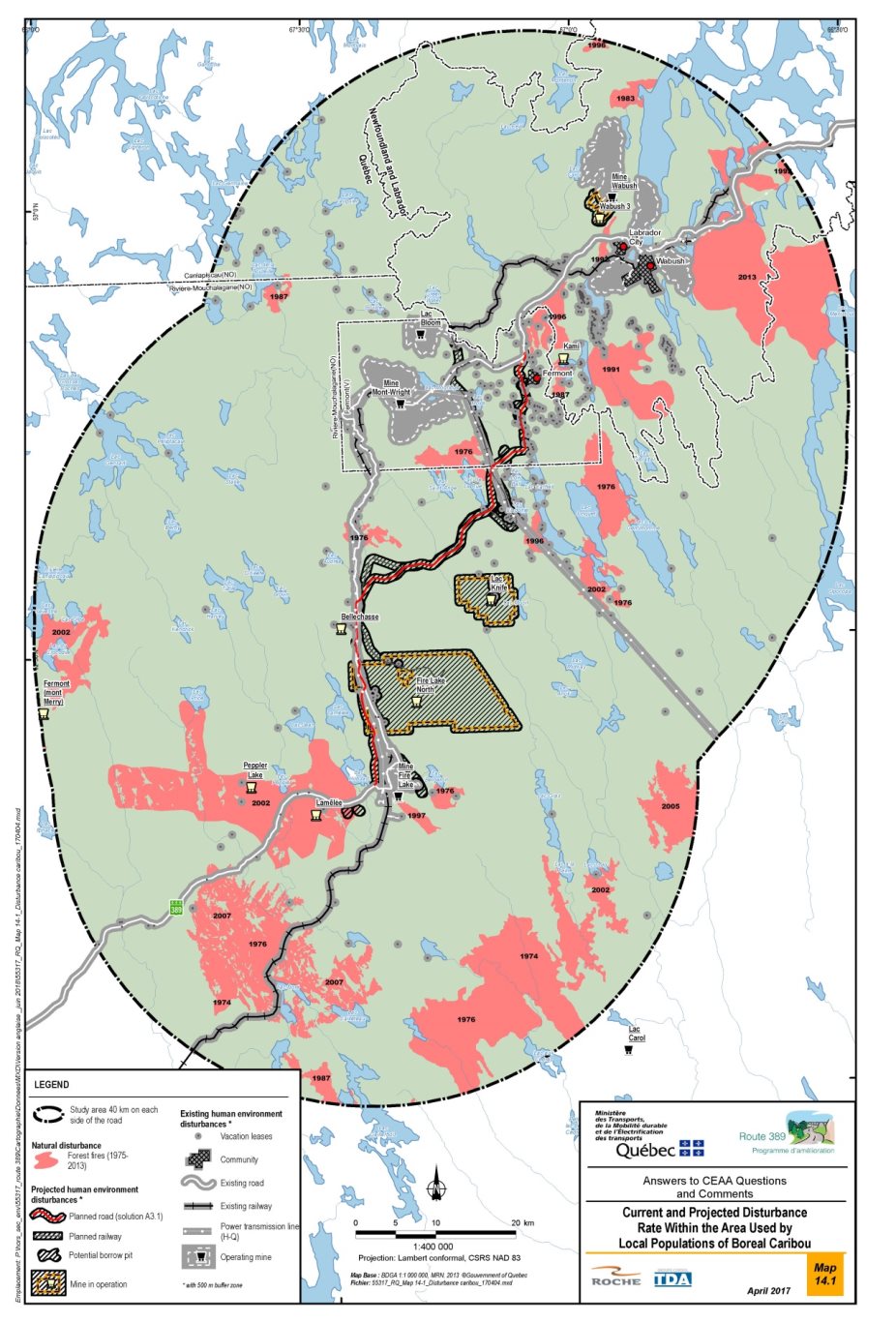

- Figure 20: Existing and projected disturbance levels in the area used by local boreal caribou populations

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Agency

- Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency

- CEAA 2012

- Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012

- Former Act

- Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (2010)

- Project

- Route 389 Improvement Project Between Fire Lake and Fermont

- Proponent

- Ministère des Transports, de la Mobilité durable et de l'Électrification des transports

- MDDELCC

- Ministère du Développement durable, de l'Environnement et de la Lutte contre les changements climatiques

- MTMDET

- Ministère des Transports, de la Mobilité durable et de l'Électrification des transports (the proponent)

- dB

- Decibel

- dBA

- A-weighted decibel

- CO2 eq

- carbon dioxide equivalent

- µg/m3

- microgram per cubic metre

- ha

- hectare

- km

- kilometre

- km/h

- kilometre per hour

- LAeq

- A-weighted equivalent continuous sound level

- LAr

- A-weighted continuous sound level to which an adjustment has been added

- PM2.5

- particles less than 2.5 microns (fine particulate matter)

- PM10

- particles less than 10 microns (fine particulate matter)

1 Introduction

1.1 Project Introduction

The Quebec Ministère des Transports, de la Mobilité durable et de l'Électrification des transports (the proponent or the MTMDET) is proposing the improvement of Route 389 between Fire Lake and Fermont to improve traffic flow and safety, enhance the link with Newfoundland and Labrador, and facilitate access to natural resources. The work includes 55.8 km of alignment on new rights-of-way and the upgrading of the existing road, for a total length of 68.9 km.

The project is part of the proponent's Route 389 Improvement Program, which covers approximately 200 km, divided into five separate projects:

- Project A: Major refurbishment and new road alignments (kilometres 478 to 564, between the Fire Lake mine and Fermont);

- Project B: Major refurbishment and new road alignment (kilometres 0 to 22, between Baie-Comeau and Manic-2);

- Project C: New road alignment (kilometres 240 to 254, north of Manic-5);

- Project D: Substandard curve corrections (kilometres 22 to 110, between Manic-2 and Manic-5); and

- Project E: Substandard curve corrections (kilometres 110 to 212, between Manic-3 and Manic-5).

This comprehensive study deals with Project A.

1.2 Purpose of the Comprehensive Study Report

This comprehensive study report summarizes the information and analyses that the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (the Agency) considered in determining whether the project may have significant adverse environmental effects as set out in the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (S.C. 1992, c. 37) (the former Act), after taking into account the proposed mitigation measures.

The Minister of the Environment and Climate Change will consider this report and the comments from First Nations, the public, the proponent and government authorities, before making a decision on the significance of the adverse environmental effects and issuing a decision statement pursuant to the former Act. Before issuing the decision, the minister may request additional information or require additional measures to be taken. If the minister believes that the project is likely to have significant adverse environmental effects, she will refer to the Governor in Council the issue of whether those effects can be justified under the circumstances. Alternatively, if the minister issues a decision statement that the project is not likely to cause significant adverse environmental effects, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Infrastructure Canada may decide to issue authorizations under section 37 of the former Act.

1.3 Scope of Environmental Assessment

The scope of the environmental assessment establishes the framework and limits of the Agency's analysis, including the regulatory and legislative requirements for an environmental assessment, the involvement of federal authorities in the environmental assessment, the factors considered, the selection of valued components, and the analysis methodology and approach.

1.3.1 Requirements of environmental assessment

The project is subject to comprehensive study under the former Act, which has been repealed and replaced, on July 6, 2012, by the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 (CEAA 2012). The project is subject to a comprehensive study–type environmental assessment because it falls under paragraph 29(b) of the Comprehensive Study List Regulations, which reads as follows:

29 (b) The proposed construction of…an all-season public highway that will be more than 50 km in length and either will be located on a new right-of-way or will lead to a community that lacks all-season public highway access.

Under the transitional provisions of CEAA 2012, any comprehensive study of a Project commenced under the former Act before the day on which CEAA 2012 came into force must be continued and completed as if the former Act had not been repealed.

A federal environmental assessment is required because authorizations set out in the Law List Regulations may be issued by Fisheries and Oceans Canada under the Fisheries Act. Fisheries and Oceans Canada is therefore the responsible authority for this environmental assessment.

The former Act applies to federal authorities that contemplate certain actions or decisions that would enable a project to proceed in whole or in part. A federal environmental assessment is required because Fisheries and Oceans Canada will have to issue a Fisheries Act authorization in relation to the Project in accordance with paragraph 35(2)(b) of the Fisheries Act which allows the carrying on of any work, undertaking or activity that results in serious Footnote 2 harm to fish that are part of a commercial, recreational or Aboriginal fishery, or to fish that support such a fishery without contravening subsection 35(1) of the same act. The authorization is set out in the Law List Regulations. In addition, Infrastructure Canada may provide funding to the proponent under the New Building Canada Fund – Provincial-Territorial Infrastructure Component – National and Regional Projects for this project.

Because a comprehensive study type environmental assessment is required, the Agency is responsible for the environmental assessment until the comprehensive study report is provided to the Minister.

The project is not subject to an environmental review by the Government of Quebec under Division IV.1 of Quebec's Environment Quality Act.

1.3.2 Factors considered in the assessment

Pursuant to subsections 16(1) and 16(2) of the former Act, the Agency has considered the following factors:

- the purpose of the project;

- alternative means of carrying out the project that are technically and economically feasible and the environmental effects of any such alternative means;

- the environmental effects of the project, including the environmental effects of malfunctions or accidents, and any cumulative environmental effects that are likely to result from the project in combination with other projects or activities that have been or will be carried out;

- the significance of the environmental effects;

- the capacity of renewable resources that are likely to be significantly affected by the project to meet the needs of the present and those of the future;

- comments from the public that are received in accordance with the former Act and the regulations;

- measures that are technically and economically feasible and that would mitigate any significant adverse environmental effects of the project; and

- the need for, and the requirements of, any follow-up program in respect of the project.

An environmental effect, as defined in the former Act, is any change that the project may cause in the environment, including any change it may cause to a listed wildlife species, its critical habitat or the residences of individuals of that species, as those terms are defined in subsection 2(1) of the Species at Risk Act, any effect of any such changes on health and socio-economic conditions, the current use of lands and resources for traditional purposes by Aboriginal persons, or any structure, site or thing that is of historical, archaeological, paleontological or architectural significance, as well as any change to the project that may be caused by the environment.

1.3.3 Selection of valued components

The proponent's assessment of potential environmental effects focused on 21 natural and human environmental components that have a specific value or significance from a scientific, social, cultural, economic, historic, archeological or esthetic viewpoint, and on which the project is likely to have an effect.

The Agency grouped most of the environmental components into six valued components that were examined in the comprehensive study. The valued components and the rationale for their selection are shown in Table 1.

|

Valued component |

Rationale |

|---|---|

|

Atmospheric environment: Air quality, greenhouse gas emissions and sound environment |

Air quality is subject to legal protection at the provincial level under the Clean Air Regulation. Atmospheric emissions and changes to the sound environment (noise and vibrations) may affect users in the area and terrestrial, bird and aquatic wildlife. The greenhouse gas emissions contribute to climate change and have an impact on the environment. Nitrogen oxide and sulphur dioxide emissions contribute to acid rain, which also has an impact on the environment. |

|

Vegetation: Wetlands and special-status plant species |

Wetlands are important habitats for many species at risk, including the boreal caribou. Wetlands are used by First Nations for their current use of lands and as resources for traditional purposes. The project could result in the loss of rare and special-status plant species under the Species at Risk Act or Quebec's Act respecting threatened or vulnerable species. |

|

Fish and fish habitats: The water environment including surface water quality, aquatic and riparian vegetation, and fish species |

The project would result in changes to water quality and the water regime that could affect fish and fish habitats. Fish and fish habitats contribute to local fishing activities (including traditional fishing) and support ecological diversity. They are protected under the Fisheries Act. |

|

Birds and bird habitats: Water birds (including the waterfowl), land birds, birds of prey including special-status species and their habitat. |

The protection and conservation of migratory birds are governed by the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994. Certain species are protected under the Species at Risk Act or Quebec's Act respecting threatened or vulnerable species.. Some bird species are hunted by the users (including Firsts Nations) of the land. |

|

Terrestrial mammals and wildlife habitats: Fur-bearing animals, large wildlife, bats and their habitats |

The project would affect certain wildlife species listed in the Species at Risk Act, including woodland caribou. A number of terrestrial wildlife species are hunted by the users of the land. |

|

The current use of land and resources for traditional purposes and structures, sites or things of historical, archaeological, paleontological or architectural significance |

The project would have an impact on users of the land for traditional purposes, the resources they use and the activities they pursue, including hunting, fishing, trapping and gathering. In addition, the project could affect the accessibility and use of homes, trails and cultural and spiritual places. The project may also affect historic or archaeological sites of importance to First Nations. |

1.4 Methodology and Approach

1.4.1 Spatial boundaries

Spatial boundaries identify the geographic areas in which the potential effects of the project would likely occur.

The spatial boundaries defined by the proponent are considered appropriate by the Agency and have been used in assessing the potential environmental effects of the project. In general, the proponent has defined a study area 300 m wide on either side of the road alignment, for a corridor of 600 m, together with the area of the proposed borrow pits. The proponent considers this study area to be large enough to limit the environmental effects of the project on most of the valued components. The proponent has defined specific spatial boundaries for assessing certain environmental components because their functional area, or "ecosystem unit," extends beyond 600 m. The components include wetlands, air, birds of prey, fish and fish habitat, large wildlife, and the current use of lands and resources for traditional purposes. Appendix A shows the study area on which the impact analysis for each valued component was focused.

1.4.2 Temporal boundaries

Temporal boundaries have been set to account for all project activities that may adversely affect the environment. For the purposes of this environmental assessment, the temporal boundaries include the total life of the project, including the road construction and operation phases. No closures are expected since the proponent plans to maintain the road as it is operated.

The Agency has found that the temporal boundaries set by the proponent are appropriate for assessing the potential environmental effects of the project. The temporal boundaries for the assessment are as follows:

Construction: Four years following six months of deforestation and site preparation

Operation: Starts after construction and continues indefinitely.

1.4.3 Impact assessment

The Agency has reviewed the environmental impact statement, additional information from the proponent, comments from the public and First Nations, and opinions of federal and provincial experts. The Agency has also reviewed the potential environmental effects on the selected valued components and determined the significance of any residual adverse effects that may occur, taking into account the implementation of mitigation measures and a follow-up program. The mitigation measures that the proponent is committed to implementing are described in Appendix B.

The significance of environmental effects is determined on the basis of scientific data, Indigenous traditional knowledge, professional judgment and other factors. The Agency also relied on federal and provincial regulatory standards and guidelines (Appendix C). To decide on the significance of the residual effects, the Agency used the intensity, extent and duration criteria defined in Appendix D.

The matrix for determining the significance of environmental effects is presented in Appendix E. It characterizes the significance of effects in terms of three levels, namely high, medium and low. High-level environmental effects are considered significant by the Agency, while medium- and low-level effects are considered insignificant. Appendix F summarizes the valued components, the environmental effects and the Agency's conclusions on the significance of residual environmental effects. The directions of the follow-up program proposed by the proponent are presented in Chapter 9.

2 Project Overview

2.1 Project Location

The Route 389 improvement project between Fire Lake and Fermont would be located in the administrative region of Nord-du-Québec, in the Caniapiscau Regional County Municipality. The northern section of the road would be located in the municipality of Fermont and the rest would be in the unorganized territory of Rivière-Mouchalagane (Figure 1). The geographical coordinates of the southern boundary would be 52°20′55″N, 67°24′33″W, and those of the northern boundary would be 52°49′33″N, 67°06′20″W.

Source: MTMDET, 2015, page 5

2.2 Project Components

The project components are as follows:

- A low-volume road (fewer than 500 vehicles per day) with a total length of 68.9 km, including 55.8 km of alignment on new rights-of-way and the upgrading of the existing road. The road's features include the following:

- ? The road will be paved at the beginning and end of the alignment, kilometres 476 to 478.6 and kilometres 541.8 to 546.85. The middle portion of the road will be gravel.

- ? The width of the new rights-of-way will vary depending on the profile of the land and the road, but it is generally expected to be between 30 m and 35 m.

- ? The design speed is 90 km/h; however, some horizontal and vertical curves Footnote 3 could not be standardized for that speed because of technical or economic constraints.

- ? Slow lanes (approximately 13 km) and runaway lanes Footnote 4 (one every 10 km for a total of 8 km of runaway lane) are planned for purposes of traffic flow and safety.

- ? Side ditches and off-take ditches would be used to manage roadway runoff.

- Water crossings, namely 23 culverts and six bridges, with the largest structures being located on Lac De La Rue, Rivière aux Pékans and Petite rivière Manicouagan.

- Waste areas for excavated and non-reusable materials.

- Two temporary camps for 75 to 100 people.

Temporary facilities or infrastructure required for construction, such as coffer dams, access roads, work areas and storage areas.

2.3 Project Activities

The activities required to carry out the project are detailed in Table 2.

|

Phase |

Activities |

|---|---|

|

Construction (four years) |

|

|

Operation (indefinite period after construction): |

|

3 Purpose of and Need for the Project, Project Alternatives, and Alternative Means AnalysisFootnote 5

3.1 Purpose of and Need for the Project

The project is part of the Route 389 Improvement Program (the program) whose main objectives are to improve the safety and traffic flow of Route 389, enhance the link with Newfoundland and Labrador, and facilitate access to the region's natural resources.

Of the five projects in the program, this project is a priority because it serves Fermont, the second largest urban area of this program. The existing Route 389 has numerous deficiencies between kilometre 478 and the Mont-Wright mine (kilometre 547.75) in part because it was built in 1978 without following specific standards to access resources by various stakeholders (Hydro-Québec and forestry and mining companies).

The proponent's rationale for the project is based on a number of factors related to road safety, the development of mining and recreational tourism, and the wishes of the municipality and the community.

Road safety and non-compliance

Safety on the existing Route 389 is in question because the geometry and curves are non-compliant and many of the level crossings do not meet current MTMDET standards. The proponent states that 33% of the 76 accidents reported between January 2006 and December 2010 were attributable to poor road conditions and to improper alignment.

The roadbed has unclear and inconsistent lane and shoulder widths. A number of segments of the existing road lack ditches or have ditches that are too shallow. Furthermore, there are no "official" slow lanes or passing lanes.

A number of road segments have excessively steep slopes, which are a risk factor for heavy transport in particular. The proponent also states that over 90% of the 1,173 vertical curves and 94% of the 379 horizontal curves in the existing highway fail to meet visibility standards. Moreover, aside from the paved section, there are virtually no guardrails on the existing road.

The existing highway has 11 level crossings, 6 of which fail to meet current railway requirements in that the angle of intersection with the highway is unacceptable or the gradient at the approach to the crossings is too steep.

Development of mining

The economy of the study area is dominated by the resource sector, which includes the iron ore mining industry. The share of resource sector jobs is 48.3% in Fermont and 36.0% in Labrador City, well above the Quebec average of less than 4%.

Several mining companies are active in the areas of Fermont and Labrador West, including ArcelorMittal and Cliffs Natural Resources, Champion Iron Mines, and Rio Tinto Iron Ore.

The proponent also refers to mining development and exploration projects such as Fire Lake North by Champion Iron Mines. Other iron and graphite mines are being studied around Lac Knife and Lac Lamêlée by Focus Graphite, Nevada Resources Corporation, Fancamp Exploration Ltd. and Cliffs Naturals Resources, and Standard Graphite. In Labrador West, the main project is the Kami iron mine developed by Alderon Iron Ore Corp.

According to the promoter, although rail transport is the cornerstone for mining activities, road transport remains an important support and it seems crucial to support it with safe and sustainable infrastructure.

Development of recreational tourism

The construction of Route 389 on a new right-of-way would provide access to areas that are already used for recreation and tourism (for example vacationing, hunting, fishing, snowmobiling and quad biking) or that are identified by the Caniapiscau Regional County Municipality as being or potentially being used for recreation and tourism. Accordingly, Project A is seen as a tool for enhancing or developing recreational tourism activities in the Fermont area.

Wishes of the municipality and community

The proponent states that the relocation of Route 389 onto a new right-of-way has been advocated for decades in various forums by elected officials, businesses, workers' unions and Fermont residents. In its development plan, the Caniapiscau Regional County Municipality supports the replacement of the existing Route 389 with a new alignment. The proponent states that there is broad consensus in the community regarding the project.

3.2 Project Alternatives

Project alternatives are functionally different ways of meeting the need for the project and fulfilling the purpose of the project. The proponent has assessed Footnote 6 three alternatives, namely the status quo (Option 1), an upgrade of the existing Route 389 (Option 2) and a new highway (Option 3) (Figure 2).

The promoter performed a multicriteria analysis using three groups of criteria, namely safety, traffic flow, accessibility and maintenance with a weighting of 45%, natural and human environments with a weighting of 40%, and socioeconomic aspects with a weighting of 20%Footnote 7. To rank the various alternatives, the proponent used the 37 criteria in the table in Appendix H.

The proponent's analysis approach for selecting an alternative consists of the following steps:

- establish a scale from 1 to 5 for each criterion;

- determine a weighting for each criterion;

- measure each criterion;

- rank the result of each criterion on the scale;

- determine the weighted % result;

- sum the weighted results for each alternative; and

- compare the sum of the weighted results to choose an option.

A summary of the proponent's analysis is presented in the subsections that follow.

Source: MTMDET, 2015, p. 255.

3.2.1 Option 1: Status quo

Option 1 would be to keep the existing Route 389 as is between Fire Lake and Fermont, without correction or improvement. This option can be divided into three segments, from south to north:

- Segment 1 (kilometres 478 to 480—the Fire Lake mine area): paved road;

- Segment 2 (kilometres 480 to 547.75—between Fire Lake and Mont-Wright): approximately 67 km of gravel road with several technical deficiencies as described in 3.1; and

- Segment 3 (kilometres 547.75 to 566—between Mont-Wright and the Fermont area): approximately 18 km of paved road with fewer deficiencies than Segment 2.

This option would not involve any change in the alignment. The only work would be road maintenance and the gradual replacement of water crossings (for example culverts) when required. However, this solution would involve maintaining the defects and irregularities of the existing roadway that currently compromise user safety and hinder traffic flow.

This option would cause the least disruption to the natural environment since it would not involve enlargement work and that no new terrestrial natural environment would be disturbed.

Economically, Option 1 would have no construction cost, but would have higher maintenance costs, namely $3.56 million per year, compared with $2.71 million for Option 2 and $2.27 million for Option 3 (Appendix H).

3.2.2 Option 2: Upgrade of the existing Route 389

Option 2 would be to correct and improve the current road alignment and profile to meet the standards of a national highway with a posted speed of 90 km/h, however certain sections would be limited to 70 km/h for technical and economic reasons. This option would result in a projected highway of 82 km, 5 km shorter than the existing highway. The segments are the same as in Option 1, and the work would be as follows:

- Segment 1: refurbishment of the existing paved section according to current standards;

- Segment 2: upgrade to roadway standards involving a near-complete reconstruction of the existing roadway, including the replacement of culverts, improved drainage and the construction of a new pavement structure; and

- Segment 3: refurbishment of the existing paved section according to current standards and the correction of substandard curves.

This option would achieve the project objectives defined in Section 3.1 (purpose of the project). However, the proponent believes that certain areas of the road could not be totally compliant with current MTMDET standards for technical, environmental impact or economic impact reasons. The road would now have five grade crossings, of which three are new for solution 2 compared to 11 level crossings for option 1.

The proponent believes that option 2 would have less impact on the natural environment compare to option 3 since it would salvage a greater part of the existing highway. However, some terrestrial habitats, wetlands and aquatic environments near the existing highway could be affected by the refurbishment of sections, bridge and culvert modifications or refurbishment and by its widening of the highway. The proponent states that a 23.5 km stretch of the existing highway is within 60 m of a body of water. Option 2 could affect the natural habitats on a stretch of 31 km and a cumulative 0.9 linear km of wetlands.

Economically, the proponent estimates the construction cost and maintenance cost for Option 2 at $181 million and $2.71 million, respectively. Those costs would be higher than those for Option 3, at $169 million and $2.27 million, respectively (Appendix H).

With respect to social acceptability, the proponent states that Option 2 does not avoid the busier area of the Mont-Wright mine. As well, the savings in time and money would be less for users since the road would be 18 km longer.

3.2.3 Option 3: New highway

Option 3 would be the construction of an entirely new highway between Fire Lake and Fermont, in addition to a major upgrade of part of the existing alignment. The total length of the proposed highway would be 68.9 km. As a result of this solution, the existing alignment between the Fire Lake mine and the Mont-Wright mine would be abandoned. In this case, the work is divided into three new segments as follows, from south to north:

- Segment 1: Between kilometres 478 and 491, the proposed Route 389 would branch north onto a new right-of-way to meet the existing road at approximately kilometre 497. The length of Segment 1 would be approximately 13 km.

- Segment 2: Between kilometres 491 and 502, the proposed Route 389 essentially follows the path of the existing road. The length of Segment 2 would be approximately 11 km.

- Segment 3: Between kilometres 502 and 546, the proposed Route 389 would branch northeast onto a new right-of-way, cross the Rivière aux Pékans and Lac De La Rue, bypass Lac Low Ball to the north, then follow an existing road linking Lac Carheil to Fermont, before bypassing Fermont to the west and rejoining Route 389. A new road link with Fermont is planned, connecting the proposed Route 389 with the existing Duchesneau Street. The length of Segment 3 would be approximately 45 km.

The proponent considers options 3 and 2 to be similar for most of the criteria related to safety, traffic flow and maintenance. Option 3 would, however, reduce the number of level crossings from 11 (currently) to 3. It would also have more guardrails to reduce the impact on vehicles and their occupants if the vehicle accidentally runs off the road (Appendix H).

Environmentally speaking, the proponent states that Option 3 is designed to avoid sensitive areas such as aquatic environments and wetlands as much as possible. However, this option would cut across an undisturbed area, thereby fragmenting the habitat of terrestrial wildlife, particularly boreal caribou.

In terms of social acceptability, a survey conducted by the proponent at an open house in Fermont shows that almost all the respondents are in favour of a new highway for the following main reasons: time and money savings resulting from the new route being approximately 18 km shorter than the existing route, a smaller number of railway crossings and the new section's straight alignment, which will provide many opportunities for passing heavy vehicles.

The proponent noted that Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants also referred to the hunting and fishing access that Option 3 would provide. The proponent believes that recreational activities related to wildlife and nature are an important aspect of the quality of life in northern communities and are a major part of the life of the people of Fermont. The proponent states that the new highway would make it easier for non-Indigenous people to use and access the land and would enable the development of recreational tourism and industry. However, this option would have a greater impact on the current use of land and resources by Innu First Nations people.

Economically, Option 3 has lower construction and maintenance costs than Option 2, as noted above.

3.2.4 Choosing an option

The table in Appendix I summarizes the proponent's assessment of project alternatives by ranking them according to safety, traffic flow, accessibility and maintenance, and respect for the natural and socioeconomic environment.

The results of the analysis show that Option 3, with an overall score of 77.8%, is better than Option 2, with 65.6%, and Option 1, with 51% (Table 3 and Appendix I).

According to the proponent's analysis, although Option 1 is the most economical, it is the lowest ranked because it does not meet one of the main objectives of the project, namely to make the highway safer. The promoter has chosen Option 3, which is ranked higher overall than Option 2. Although their results are comparable in terms of technical criteria (36.4% versus 37.6%), Option 3 would have a clear advantage in terms of socioeconomic aspects (15.5% versus 8.4%) (Appendix I).

|

Criteria (weighting) |

Option 1 (Status quo) |

Option 2 (Upgrade of the existing highway) |

Option 3 (New highway) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Safety, traffic flow, accessibility and maintenance (45%) |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

Natural and human environments (40%) |

2 |

3 |

1 |

|

Economics |

1 |

3 |

2 |

|

Total (105%) |

3 |

2 |

1 |

3.3 Alternative Means Assessment

Under the former Act, it is also required to examine alternative means of carrying out the project that technically and economically feasible and to examine the environmental effects of those alternative means.

The alignment variants A, B, C and D identified for the analysis are variations in the layout and profile of the chosen option, generally over a single length of less than 10 km. The proponent has compared the variants with the chosen option (Section 3.2.4) based on the technical, environmental and economic criteria in Table 4.

|

Aspect |

Criteria |

|---|---|

|

Technical |

|

|

Environmental |

|

|

Economic |

|

Having completed the analysis, the proponent has decided not to adopt any of those variants but rather to optimize the chosen option. The proponent believes that the chosen option would result in significant gains in terms of road safety, traffic control and management during construction, and the environment.

Detailed variant analysis results can be found in Appendix J, and the following subsections summarize the advantages and disadvantages of the four alignment variants analyzed by the proponent in comparison with the chosen option.

3.3.1 Variant A

Variant A starts approximately 4 km north of kilometre 478 of the existing highway and lies between kilometres 481.7 and 491.3 of the chosen option (Figure 3). Starting at kilometre 481.7, this variant would branch northeast to meet the existing road shortly after kilometre 489. The alignment would generally follow the existing highway, except for an additional curve shortly before kilometre 490.

Variant A has the following advantages over the chosen option:

- two non-compliant 100 km/h vertical curves versus four;

- significantly less excavated material;

- terrestrial habitat losses of 26.65 ha versus 42.38 ha; and

- wetland losses of 0.36 ha versus 0.93 ha.

However, Variant A has the following disadvantages:

- total length of 10.18 km, 580 m longer than the chosen option;

- two level crossings, whereas the chosen option would not have any;

- 10 horizontal curves that fail to meet MTMDET standards for a design speed of 100 km/h, whereas the chosen option would have none;

- opportunities for passing along 0.8 km versus 3.7 km;

- four water crossings versus three;

- encroachment into 15 280 m² of fish habitats versus 210 m²; and

- more difficult traffic control during construction.

The proponent states that Variant A would be similar to the chosen option in terms of construction costs and the impact on Hydro-Québec's power lines, which would be encountered once.

Source: provided by MTMDET

3.3.2 Variant B

Variant B lies between kilometres 498.6 and 502.6 of the chosen option, but instead of continuing north onto new rights-of-way, this variant would run along the existing Route 389 (Figure 4).

Variant B, which is similar in length to the chosen option (3.96 km versus 4.02 km), has a few advantages, including fewer non-compliant curves (two versus three), a smaller loss of terrestrial habitats (9.56 ha versus 18.56 ha) and a 50% smaller volume of excavated material.

However, Variant B would have a number of disadvantages compared with the chosen option:

- location closer to the railway;

- more encroachments into lakes (2 300 m² versus 660 m²);

- more filling of wetlands (0.53 ha versus 0.20 ha);

- 10% higher construction costs; and

- more difficult traffic control during construction.

Source: provided by MTMDET

3.3.3 Variant C

Variant C lies between kilometres 517.3 and 530.65 of the chosen option (at the northern end of Lac Low Ball) (Figure 5).

The analysis shows that Variant C is similar to the chosen option in terms of lost wetlands (0.96 ha versus 1.08 ha) and terrestrial habitats.

Variant C, which is 15.9 km long, has a few advantages over the chosen option:

- no non-compliant curves; and

- fewer water crossing structures (four versus six).

However, Variant C has the following disadvantages:

- a length that is 2.57 km greater;

- a greater loss of fish habitats (730 m² versus 470 m²); and

- 15 % higher construction costs.

Variant C would cross Lac De La Rue about 3 km southeast of the chosen option, where it is narrower, which would mean building a less expensive bridge. However, as Variant C is 2.57 km longer, its overall construction cost would be higher.

Source: provided by MTMDET

3.3.4 Variant D

Variant D is located at the junction with the existing Route 389 at the northern boundary of the project, between kilometres 543.6 and 546.9, to the north of the chosen option (Figure 6).

Variant D and the chosen option are similar in length (3.14 km versus 3.04 km) and in terms of encroachment into fish habitats (140 m²).

Variant D has no encroachment into wetlands, compared with 0.31 ha for the chosen option. However, it would have a number of disadvantages:

- reduced safety in the approaches to the Claude Ménard Boulevard intersection;

- slightly greater loss of terrestrial habitats (11.72 ha versus 11.23 ha);

- 14% higher construction costs; and

- the relocation of a number of Hydro-Québec transmission line towers.

Source: provided by MTMDET

3.4 Comments Received

Federal authorities

The Agency has not received comments from federal authorities regarding the purpose of the project, project alternatives and alternative means analysis.

Public

The Agency has not received comments from the public regarding the purpose of the project, project alternatives and alternative means analysis.

First Nations

The Innu First Nation of Uashat mak Mani-Utenam raised concerns about the lack of real consultation by the proponent regarding the chosen option of building a highway on new rights-of-way that would open up the area and divide their claimed ancestral land (Nitassinan).

As for the alternative means analysis, the Innu First Nation of Uashat mak Mani-Utenam believes that choosing Variant A would have made it possible to use the rights-of-way of the existing highway and choosing Variant C would have avoided cutting through Lac De La Rue.

The proponent states that it consulted with First Nations as part of the project and that the chosen option is the most advantageous based on 37 criteria, including the impacts of the project on First Nations.

3.5 Agency's Analysis and Conclusion

The Agency is satisfied that the proponent has sufficiently assessed alternative means of carrying out the project for the purposes of assessing the environmental effects of the project under the former Act.

The proponent has provided the requested information, presenting alternatives to the project and discussing the environmental, technical and economic advantages and disadvantages of each option. In addition, the proponent has explained the approach used to rank the project alternatives and arrive at the chosen option, namely constructing the highway on new rights-of-way.

The proponent then analyzed four alignment variants on different sections of the chosen option. The Agency considers the proponent's criteria and variant analysis to be adequate.

4 Consultation Activities and Advice Received

Public and First Nations consultations enhance the quality and credibility of environmental assessments. The comments and concerns received through consultations help to clarify the potential effects of a project, beginning at the planning stage. As part of the Route 389 improvement project between Fire Lake and Fermont, the Agency, in co-operation with the federal environmental assessment committee, conducted a number of consultations with the public and First Nations.

4.1 Consultation with First Nations

4.1.1 Agency's consultation with First Nations

The federal government has a duty to consult and, where appropriate, accommodate Indigenous people when considering decisions that may adversely affect established or potential Indigenous or treaty rights. Indigenous consultation is also undertaken more broadly as an important part of good governance, policy development, and informed decision making. In addition, the former Act requires that all federal environmental assessments take into account the effects of the project either on the current use of lands and resources for traditional purposes by Indigenous peoples, or on a structure, site or thing of historical, archaeological, paleontological or architectural significance.

For the purposes of this environmental assessment, the Agency coordinated federal Crown consultations and consulted the Innu First Nation of Matimekush–Lac John, the Innu Nation (Labrador), and the Innu First Nation of Uashat mak Mani-Utenam Footnote 8. For good governance purposes, the Agency also informed Innu First Nation of Pessamit of the major steps in the environmental assessment.

The Agency did not have a consultation plan with Innu Nation as the Innu of Labrador are relatively far from the study area and did not provide any comments on the adverse effects that the project might have on their claimed rights. However, the Agency kept the First Nation informed of the major stages of the environmental assessment.

The Agency agreed with the Council of Innu First Nations of Matimekush–Lac John and of Uashat mak Mani-Utenam on consultation plans that included participation in various stages of the environmental assessment. By the end of the comprehensive study process, the First Nations will have had three formal opportunities for consultation.

The Agency supports First Nations participation through the Participant Funding Program. As part of the comprehensive study, the Agency allocated a total of $114,528 to the two First Nations that applied for funding, namely the Innu First Nations of Matimekush–Lac John and Uashat mak Mani-Utenam.

Throughout the environmental assessment process, the Agency has maintained regular contact with First Nations. To announce the three consultation opportunities, the Agency notified the relevant band councils in correspondence and placed notices in the newspaper Innuvelle.

During the first consultation opportunity (May 24 to June 26, 2012), for comments on the draft guidelines for the proponent, the Agency received comments from the Innu First Nation of Uashat mak Mani-Utenam, specifically on the consultation approach of the Agency and the proponent.

During the second consultation period (January 25 to February 24, 2016), on the summary of the environmental impact statement, First Nations were invited to comment on the environmental effects of the project, the impacts on claimed or treaty rights, and the accuracy of the information provided by the proponent in the environmental impact statement. The Agency held a meeting with the councils of the Innu Nations of Matimekush–Lac John (February 25, 2016) and Uashat mak Mani-Utenam (June 15, 2016). The Agency and representatives of the Federal Environmental Assessment Committee also met with members of the community and of the Grégoire family in Sept-Îles on June 15, 2016. These meetings enabled First Nations members to discuss their various concerns regarding the project with representatives of the Agency and the federal environmental assessment committee. Comments received at these meetings helped guide the Agency's review of the environmental impact statement and highlighted the need for additional information from the proponent to better assess the effects of the project.

During the second consultation period, the Innu First Nations of Uashat mak Mani-Utenam and Matimekush–Lac John submitted briefs to the Agency describing the use of the land and the potential impacts of the project on that use. The issues raised include the maintenance of traditional activities, access to their traditional territory and its availability to non-Indigenous people, the preservation of the Innu archaeological and cultural heritage, the effects on the sacred Moisie River, the economic opportunities related to the project and the effects on wildlife, particularly woodland caribou.

For the third consultation period, the Agency is inviting First Nations to provide comments on the content, conclusions and recommendations of this comprehensive study report. The Agency will present the comments received to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change to inform a decision on the environmental assessment of this project.

The effects of the project on the current use of lands and resources by First Nations are discussed in Section 6.6, and the implications for established or potential Indigenous and treaty rights are discussed in Chapter 8. Appendix F summarizes the concerns raised by First Nations during the environmental assessment process and includes the responses of the proponent and the Agency. Subsequent comments from First Nations will be provided to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change to inform her decision on the environmental assessment.

Following the Minister's decision on the environmental assessment, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, as the responsible authority for the project, may consult the affected First Nations regarding authorizations to be issued under the Fisheries Act for the implementation of the project, including fish habitat compensation projects.

The Agency will submit comments received to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change Canada to inform its decision regarding the environmental assessment of this project. If the environmental assessment decision is favorable, Fisheries and Oceans Canada could issue an authorization or authorizations under paragraph 35 (2) (b) of the Fisheries Act for the project. If this is the case, a specific consultation process will be initiated by Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

4.1.2 Proponent's consultation with First Nations

The proponent consulted the Innu First Nations of Uashat mak Mani-Utenam and Matimekush–Lac John and Pessamit in preparing the environmental impact statement and the environmental assessment for the project.

In particular, the proponent met with the Uashat mak Mani-Utenam and Pessamit band councils in 2013 and organized an "open house" in the Uashat mak Mani-Utenam community in May 2014, in addition to meeting in 2016 with the main users of the land who might be affected by the project. The proponent also consulted with the Innu Nation of Matimekush–Lac John, meeting with the band council and organizing a town hall meeting in February 2017. The issues raised at the meetings held by the proponent were similar to those raised during the Agency's consultations.

Note that the proponent attended meetings arranged by the Agency on June 15, 2016, with the Uashat mak Mani-Utenam First Nation and the community.

4.2 Public Consultation

4.2.1 Agency's public consultation

The environmental assessment process completed under the former Act provides for three periods of public participation, namely during the preparation of the environmental impact statement guidelines, the environmental impact statement analysis and the release of the comprehensive study report.

To announce the first two stages of public participation, the Agency posted notices on the Canadian Environmental Assessment Registry website and in various newspapers, and placed radio spots on local stations. Documents relevant to the consultations were added to the Canadian Environmental Assessment Registry website and hard copies were made available at various public places in communities near the project.

The first consultation, held by the Agency from May 24 to June 26, 2012, was to obtain comments on the draft guidelines for the proponent. During this initial consultation, the Agency did not receive any comments from the public.

The second consultation, from January 25 to February 24, 2016, was an opportunity for those interested to comment on the potential environmental effects of the project and the mitigation measures proposed by the proponent in its environmental impact statement. During this second consultation, the Agency did not receive any comments from the public.

For the third consultation period, the Agency is inviting the public to comment on the content, conclusions and recommendations of this comprehensive study report. The Agency will submit this report to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change to inform her decision regarding the environmental assessment of this project.

4.2.2 Proponent's public participation activities

Starting in 2011, the proponent undertook information and consultation activities primarily targeting elected officials of the regional county municipalities of Caniapiscau and Manicouagan, environmental organizations, the general public, and the Innu First Nations of Matimekush–Lac John, Pessamit and Uashat mak Mani-Utenam. The proponent states that the purpose of the meetings was to outline the Route 389 improvement program and the aspects associated with the various projects (for example construction work, schedules and budgets), to establish a collaborative relationship with stakeholders and determine the means of communicating with them, and to hear the attendees' questions, comments and concerns.

Among other things, the proponent held open houses between September 2013 and May 2014 in Baie-Comeau, Fermont, Pessamit and Sept-Îles. The purpose of the open houses was to establish more direct contact with the public, to compile the public's general comments and concerns about the projects, and to find out the public's preferred alternatives. A total of 162 people attended the open houses. The proponent states that the days made it possible to confirm the public's support for the Route 389 improvement program and the participants' agreement on the choices made. Some participants allegedly expressed concern that the timelines were too long.

4.3 Participation of Federal Government and Other Experts

Federal government departments provided expert information or knowledge relevant to the project in accordance with subsection 12(3) of the former Act.

The following federal authorities provided opinions related to the guidelines, the review of the proponent's environmental impact statement and the preparation of this comprehensive study report: Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Infrastructure Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada, and Health Canada. Some of these federal authorities also helped with planning and conducting consultations with First Nations throughout the federal environmental assessment process.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada, which has regulatory and legal responsibilities under the Fisheries Act, provided comments and information on potential adverse effects of the project on fish and fish habitats. As part of the environmental assessment, Fisheries and Oceans Canada has stated that the proponent would require an authorization or authorizations under the Fisheries Act to carry out the project.

Infrastructure Canada may provide funding to the proponent under the New Building Canada Fund – Provincial-Territorial Infrastructure Component – National and Regional Projects for this project.

Environment and Climate Change Canada has regulatory and legal responsibilities under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994, the Species at Risk Act and the pollution prevention provisions of the Fisheries Act. Environment and Climate Change Canada has provided comments and information on potential adverse effects of the project on migratory birds and bird habitats, species at risk, water quality, air quality, chemicals management, and environmental emergencies.

Health Canada has provided comments and information on potential adverse effects on human health that may result from changes in air and water quality, in the sound environment, and from the contamination of traditional food.

The Agency also worked with provincial experts from the Quebec Ministère de la faune et des parcs (MFFP) and the Ministère du Développement durable, de l'Environnement et des Changements climatiques (MDDELCC) which have provided advice on special-status species, namely boreal caribou and brown-edged pussytoes.

5 Geographical Setting

5.1 Biophysical Environment

The project would be located in the Canadian Shield, specifically in the northern part of the geologic province of Grenville. The study area covers the Fermont Iron Ore District, which is located in a major geological belt called the Labrador Trough and which is known for its significant iron ore reserves.

The surface of the soil is characterized by deposits resulting from the retreat of the Laurentide Ice Sheet during the last glaciation. Otherwise, the soil is mainly Precambrian-age metamorphic and igneous rocks. These are not very permeable, but significant fracture zones are present in the region and could potentially serve as preferential corridors for groundwater flow.

The area is part of the high lake plateau of Côte-Nord. The project would cross three watersheds, namely Petite rivière Manicouagan, Rivière aux Pékans and Lac Carheil. The topography is rather flat and there are numerous lakes, some large, such as Lac Carheil and Lac De La Rue. The area is crossed by several watercourses that are part of the large watershed of the Moisie River. The Government of Quebec plans to create an aquatic reserve on the Moisie River that will be subject to "strict protection"Footnote 9 to preserve its biodiversity while allowing recreational access to the public. For now, this reserve has temporary protection until 2025, which prevent mining and industrial exploitation. The project would cross this reserve over a distance of approximately 11 km (Figure 7). The proponent has sampled various watercourses that the project will cross and states that the physical and chemical quality of the water observed (pH, conductivity, turbidity, temperature and dissolved oxygen) varies greatly.Footnote 10

The region is dominated by a cold, moderately wet subpolar climate with a relatively short growing season. The average annual temperature hovers around −3.9°C. Winters are long, cold and dry, while summers are short.

The vegetation in the study area is 67% dominated by the eastern subdomain of the spruce-moss forest and 33% covered by the domain of the spruce-lichen forest. Black spruce (Picea mariana) is predominant and is occasionally accompanied by balsam fir (Abies balsamea) and tamarack (Larix laricina).

Of the wetlands present, peatlands are the most abundant: 94% of wetlands are peatlands, 5.5% are swamps and 0.4% are marshes. The peatlands cover 4.3% of the study area and are found mainly at the bottom of valleys and along watercourses.

The data sent to the proponent by the Centre de données sur le patrimoine naturel du Québec have revealed that references have been made to plants in the study area that are likely to be designated as threatened or vulnerable. The brown-edged pussytoes (Antennaria rosea subsp. confinis) is the only special-status vascular species reported by the Centre de données sur le patrimoine naturel du Québec that was observed in 2001 on either side of Route 38 at 60 km south of Fermont.

With regard to wildlife, the presence of 4 species of amphibians, 12 species of fish, 21 species of mammals and 54 species of birds was confirmed on the site during the inventory conducted by the proponent. The ranges of the little brown myotis and the northern myotis, designated "endangered" under the Species at Risk Act, cover the study area. The proponent did not conduct an inventory of bats. However, an assessment of the potential for presence during the breeding, migration and overwintering periods was conducted using the information available on these species and on the habitats present in the study area.

None of the species of amphibians or fish which were observed in the study area have special status at the federal or provincial level (COSEWIC, 2013). Of the mammals for which sightings were confirmed, the rock vole and Cooper's lemming vole are likely to be designated as threatened or vulnerable on the MDDELCC's list of species likely to be designated as threatened or vulnerable. Boreal caribou, present in the area, are considered threatened in Canada under the Species at Risk Act and vulnerable in Quebec under the Act respecting threatened or vulnerable species. The wolverine has a special concern status in Canada (Species at Risk Act) and the pygmy weasel is a vulnerable species in Quebec. These two species were not observed in the study area.

Of the bird species at risk listed in Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act and potentially present in the study area, the olive-sided flycatcher, bank swallow, rusty blackbird and common nighthawk have been confirmed. However, the presence of the anatum subspecies of peregrine falcon, harlequin duck, barn swallows and short-eared owl was not confirmed during the inventories. Finally, the presence of the bald eagle, designated as "vulnerable" under the Act respecting threatened or vulnerable species, was observed in the study area but its nesting has not been confirmed.

5.2 Human Environment

The main demographic and economic characteristics of the study area correspond to those of Fermont, the unorganized territory of Rivière-Mouchalagane and the Caniapiscau Regional County Municipality in Quebec, and Labrador City, Wabush and Economic Zone 2 in Newfoundland and Labrador. In Statistics Canada's 2016 Census, the populations of Fermont, Labrador City and Wabush were 2,288, 8,622 and 1,906, respectively.

According to the proponent, the economy of the study area is dominated by the resource sector. According to the proponent, the participation and employment rates in Fermont and Labrador City are exceptionally high. However, the proponent states that the region's vitality is vulnerable to market fluctuations because the economy, which is based on mining, is not very diversified. Fermont is therefore seeking to diversify its economic activity through the development of new minerals, mining tourist attractions and outdoor activities.

With regard to trapping, the study area is located in the Saguenay beaver reserve, and the Innu First Nation of Uashat mak Mani-Utenam has special but not exclusive rights in the Sept-Îles division. The project passes through trapping lots of the Innu families of this First Nation, such as the Grégoire family's Lot 255. The project is located on land that is the subject of comprehensive land claim negotiations by the Innu Nations of Uashat mak Mani-Utenam and Matimekush–Lac John.

Uashat mak Mani-Utenam First Nation has 3,728 members registered as residents on the reserve. The First Nation's economy is based on the public sector. The band council, with nearly 267 permanent jobs and 600 seasonal jobs, is the main employer of the Innu of this nation and one of the largest in the Sept-Îles region.Footnote 11 According to the information collected on the website of the Nation, the Uashat and Mani-Utenam reserves have approximately 50 companies specializing in various fields such as food service, commercial fishing and seafood processing, tailoring, canoe manufacturing, campground development and management, landscaping, heavy machinery, electricity, management services, and translation.Footnote 12

The Innu First Nation of Matimekush–Lac John, which has 829 members registered as residents on the reserve,Footnote 13 is approximately 700 km north of the project study area. Information gathered during the proponent's various consultations with this First Nation confirmed that the selected road alignment crosses the main traditional Innu transportation route between Rivière aux Pékans and Wabush Lake.

6 Predicted Effects on Valued Components

6.1 Atmospheric Environment

This section presents the analysis of the project's effects on the atmospheric environment (air quality, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and ambient noise).

According to the Agency, a significant residual adverse effect on the atmospheric environment is one that would cause a high risk of exposure to air contaminants that exceed applicable standards and criteria of health protection, or an increase of noise that exceed standards or criteria of health protection, and that people are exposed to it regularly or continuously Footnote 14. For greenhouse gas emissions, only the significance of the contribution of the project is assessed. The Agency's criteria for evaluating environmental effects and the grid used to determine the significance of the effects are presented in Appendices D and E, respectively.

Based on its analysis, the Agency concludes that the project is unlikely to result in significant adverse environmental effects on the atmospheric environment, given the mitigation measures and monitoring and follow-up programs proposed by the proponent:

- The population, including First Nations, would be little exposed to the contaminants emitted by the project. The project area is not heavily developed. Increased levels of dust, metals, metalloids and other contaminants in the air are unlikely to exceed health protection standards and criteria if mitigation measures are applied properly.

- The quantity of greenhouse gas emissions generated by the project would not contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions at the provincial and national scale.

- It is unlikely that noise increases will exceed the standards and criteria for health protection.

- Greenhouse gas emissions estimated at 7,295 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2 eq) per year for the construction phase and 2,649 tonnes of CO2 eq per year in operation would not be a high contribution to provincial and national emissions.

The following subsections describe the baseline conditions and the essential elements of the proponent's analysis, present the opinions of the expert departments, the First Nations and the general public, on which the Agency based its conclusion regarding the significance of the project's effects on the atmospheric environment.

6.1.1 Baseline conditions

The proponent used the general study area to characterize air quality and noise levels. Greenhouse gas emissions were examined in a broader context, since the effects of these gases on the environment are a concern at the provincial, national and global levels.

Air quality and emissions of contaminants

To characterize air quality, the proponent used data from the National Air Pollution Surveillance Network and the National Pollutant Release Inventory. The National Air Pollution Surveillance Network is a Canada-wide network of ambient air quality sampling stations.

In order to provide a more representative picture of air quality in the study area, the proponent compiled the results from the closer stations: Chapais, Pémonca and Labrador City (Smokey Mountain). None of those stations are located directly in the study area and none has sufficient data to be able to draw an adequate portrait of the study area. For example, at the Chapais sampling station, only ozone concentration are measured; at the Pémonca station, concentrations of ozone and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) are measured. At the Labrador City station, concentrations of sulphur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), ozone and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) are measured but only data from 2014 are available.

For ozone concentrations, the data from the Chapais and Pémonca stations were compared with the standards in the Québec Regulation for the Cleaner Atmosphere (Q-2, r 4.1) and the Canadian Ambient Air Quality Standards. Thus, for Quebec standards, the one-hour maximum concentrations are occasionally exceeded and exceedances of the standard eight-hour are observed each year, but the national objective is met.

At the level of fine particles (PM2.5), the proponent compared the data from the Pémonca station with the applicable Quebec standard. Thus, for the data of the station of Pémonca, the norm in force has always been respected.

At the Labrador City station, results indicate that contaminant concentrations (SO2, NO2 and PM2.5) are below provincial and federal standards. Only ozone concentrations occasionally exceeded provincial standards (Table 5).

|

Contaminants |

Period |

Maximum value obtained (µg/m3) |

Applicable standard (µg/m3) |

Frequency of exceedance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Source: MTMDET, 2016, page 124. |

||||

|

Sulphur dioxide (SO2) |

4 minutes |

127.1 |

1,050 |

0.00 % |

|

24 hours |

10.8 |

288 |

0.00 % |

|

|

Annual |

1.51 |

52 |

0.00 % |

|

|

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) |

1 hour |

89.1 |

414 |

0.00 % |

|

24 hours |

24.6 |

207 |

0.00 % |

|

|

Annual |

0.62 |

103 |

0.00 % |

|

|

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) |

24 hours |

14 |

30 |

0.00 % |

|

Annual |

2.46 |

10 |

0.00 % |

|

|

Ozone (O3) |

1 hour |

194.5 |

160 |

0.09 % |

|

8 hours |

175.5 |

125 |

0.16 % |

|

According to the National Pollutant Release Inventory,Footnote 15 there are no large industrial emitters in the study area. The only emitter in the area which appears on the Inventory is the ArcelorMittal mine at Mont Wright. However, the route of the new road is not adjacent to the ArcelorMittal mine.

Some other mines are in the vicinity of the study area but have insufficient emissions to be included in the National Pollutant Release Inventory. However, they are sources of emissions of air contaminants. These mines include:

- The Fire Lake mine, owned by ArcelorMittal, approximately three kilometres east of existing Highway 389;

- Cliffs Natural Resources' Lake Bloom Mine near the current route of Route 389 near Fermont;

- Cliffs Natural Resources' Scully Mine, located in Labrador 17 km northeast of Fermont;

- Labrador's Carol Lake Mine, owned by Rio Tinto IOC, located 29 km north-northeast of Fermont.

Several mining projects are also under development in the study area. Emissions of air contaminants could therefore possibly come from the operations of these mines.

Greenhouse gases

Greenhouse gases are atmospheric gases that absorb and reflect infrared rays, causing warming of lower levels of the atmosphere. They are recognized as one of the causes of climate change, which can have various impacts on ecosystems and human health. The major greenhouse gases include carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), sulphur hexafluoride (SF6), ozone (O3), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and perfluorocarbons (PFCs). Estimates of greenhouse gases are normally expressed in tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents per year (CO2 eq per year).

Since the Canadian Greenhouse Gas Inventory does not identify greenhouse gas emissions for a specific region, it was not possible to provide a description of greenhouse gas emissions for the specific study area. Thus a more global description has been given.

In 2015, total greenhouse gas emissions in Canada reached 714 megatonnes CO2 eq, of which 28% (202 megatonnes CO2 eq) was generated by the transportation sector. Road transportation represented 142 Mt CO2 eq of the transportation sector's emissions, which is 19.8% of total greenhouse gas emissions (ECCC, 2018).

In 2015, total greenhouse gas emissions in Quebec reached 81.7 megatonnes CO2 eq, of which 34.0 megatonnes CO2 eq were generated by the transportation sector (road, air, maritime, rail and off-road). Road transportation made up 78.8% of emissions generated by the transportation sector and 32.8% of total greenhouse gas emissions (MDDELCC, 2018).

Noise

Based on measurements taken on August 19 and 20, 2013, at various locations in the study area, the proponent determined that daytime noise levels (LAeq) varied between 37 LAeq (1hr) and 54.5 LAeq (24hrs), to the closer homes.

The proponent indicates that road traffic is largely responsible for higher noise levels in the urban environment of Fermont. The presence of children and human activities associated with maintenance of dwellings and public spaces (e.g. tractor for park maintenance) contribute to the increased daytime noise levels. On very calm nights, the noise levels are between 25 dBA and 30 dBA.